Tutmonda varmiĝo estas nuntempe progresanta plialtiĝo de la averaĝa temperaturo de la atmosfero kaj oceanoj de la Tero kaj ties rilataj efikoj. La termino klimata ŝanĝiĝo referencas al ĉiu ajn historia ŝanĝiĝo de la klimato. Multaj linioj de scienca pruvaro montras, ke la klimata sistemo varmiĝas.[1][2] La nuntempa plialtiĝo de la tutmonda averaĝa temperaturo estas pli rapida ol antaŭaj ŝanĝoj, kaj estas okazigita ĉefe pro tio ke homoj brulas fosiliajn brulaĵojn.[3][4] Uzado de fosiliaj brulaĵoj, senarbarigo, kaj kelkaj praktikoj fare de agrikulturo kaj industrio pliigas la elsendojn de forcejaj gasoj, ĉefe de karbona dioksido kaj de metano.[5] Forcejaj gasoj absorbas iom de la varmo kiun la Tero radias post ĝi varmiĝas el la sunlumo. Plej grandaj kvantoj de tiuj gasoj kaptas pli da varmo en la malalta atmosfero de la Tero, okazigante la tutmondan varmiĝon.

Pro la klimata ŝanĝiĝo, dezertoj estas ampleksiĝantaj, dum varmondoj kaj incendioj en naturo estas iĝantaj pli kaj pli oftaj.[6] Pliiĝanta varmiĝo en Arkto estas kontribuanta al fandado de permafrosto, retiriĝo de glaĉeroj ekde 1850 kaj perdo de marglacio.[7] Pli altaj temperaturoj estas okazigintaj ankaŭ pli intensajn uraganojn, sekegon, kaj aliajn ekstremajn veterojn.[8] Rapida media ŝanĝo en montoj, koralrifoj, kaj Arkto estas pelanta multajn speciojn relokiĝi aŭ eĉ formortiĝi.[9] Eĉ se la klopodoj por malpliigi estontan varmiĝon estas sukcesaj, kelkaj efikoj pluos dum jarcentoj. Inter tiuj menciendas oceanvarmiĝo, oceana acidiĝo kaj marnivela leviĝo.[10]

La tutmonda varmiĝo minacas la popolojn per pliiĝantaj inundoj, ekstrema varmo, pliiĝanta manko de manĝaĵoj kaj de akvo, pliiĝo de malsanoj, kaj ekonomiaj perdoj. Ankaŭ homa migrado kaj tiurilataj konfliktoj povas esti rezulto de la tutmonda varmiĝo.[11] La Monda Organizaĵo pri Sano (MOS) konsideras la klimatan ŝanĝon la plej granda minaco al la tutmonda sano en la 21-a jarcento.[12] Socioj kaj ekosistemoj suferos pli severajn riskojn sen adoptado de decidoj kiuj mildigu la varmiĝon.[13] Adaptado al klimata ŝanĝiĝo pere de klopodoj kiel inundo-kontrolo aŭ uzado de sekeg-rezistaj kultivoj parte povus malpliigi la riskojn de la klimata ŝanĝo, kvankam bedaŭrinde jam oni atingis kelkajn limojn al tia adaptado.[14] Pli malriĉaj landoj estas responsaj de pli malgranda parto de la tutmondaj elsendoj, sed ankaŭ havas malpli grandan kapablon adaptiĝi kaj estas pli frapeblaj de la klimata ŝanĝo.

Multajn efikojn de la klimata ŝanĝo jam oni sentis je la nuntempa varmigonivelo de 1.2 °C. Aldona varmigo pliigos tiujn efikojn kaj povas malbonigi la endanĝerigitajn lokojn, kiel ĉe la fandado de la Gronlanda glacikovro.[15] Laŭ la Pariza interkonsento de 2015, la landoj kolektive interkonsentis teni varmigon "bone sub 2 °C". Tamen, kadre de plendoj pri la interkonsento, la tutmonda varmiĝo ankoraŭ atingos ĉirkaŭ 2.7 °C je la fino de la jarcento.[16] Limigi la varmigon al 1.5 °C postulos duonigi la elsendojn je ĉirkaŭ 2030 kaj atingi elsendojn nulajn ĉirkaŭ 2050.[17]

Malpligi elsendojn postulas generadon de elektro el fontoj kun malmulta aŭ neniu karbono anstataŭ bruligi fosiliajn brulaĵojn. Tiu ŝanĝo inkludas iompostioman malpliigon de la uzado de elektraj centraloj nutritaj el karbono kaj natura gaso, pliigon de uzado de venta, suna, nuklea energioj kaj aliaj tipoj de renovigeblaj energio, kaj reduktadon de energikonsumado. Necesas, ke elektro generita el fontoj kiuj ne elsendas karbonon anstataŭu la fosiliajn brulaĵojn por akiri energion por transportado, varmigado (respektive malvarmigado) de konstruaĵoj, kaj funkciado de industriaj instalaĵoj.[18][19] Karbono povas esti ankaŭ forigita al la atmosfero, ekzemple pere de pliigo de la arbara kovro kaj agtikulturo per metodoj kiuj kaptu karbonon en la grundon.[20]

La fenomeno

Nuntempe eblas konstati ĝeneralan varmiĝon de la atmosfero de nia planedo. En la lastaj tridek jaroj la averaĝa temperaturo sur la tergloba surfaco plialtiĝis 0,5 celsiojn. La homo kaŭzis tion per enaerigo de metano, karbona dioksido, kaj aliaj forcejaj gasoj ekde la industriigo.

La natura forceja efiko igas la atmosferon 3 celsiajn gradojn pli varma, ĉefe pro la akvovaporo, la plej grava forceja gaso. Sen konsidero de aliaj ŝanĝoj diras teorio, ke plimultigo de la karbona dioksido en la atmosfero kaŭzas plivarmigon de la planeda surfaco.

La Interregistara Komitato pri Klimata Ŝanĝiĝo de Unuiĝintaj Nacioj, subtenate de la naciaj sciencaj akademioj de la G8-ŝtatoj, esprimis sciencan prijuĝon, laŭ kiu la mezuma planeda temperaturo ekde la komenco de la 20-a jarcento plialtiĝis 0.6 ± 0.2 celsiajn gradojn kaj plej "multe el la varmiĝo observata dum la lastaj 50 jaroj estas atribuebla al homaj agadoj". Restas necerta la amplekso de la klimata ŝanĝo, kiun oni observos estonte.

Antropoceno estas proponita geologia epoko de la tera historio, kiu komenciĝus ekde la komenco de grandaj homaj influoj al geologio kaj ekosistemoj de la Tero. Unu el la plej gravaj el tiuj homaj influoj estas interalie homkaŭzita tutmonda varmiĝo.

La grado de la varmiĝo

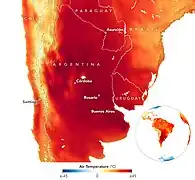

La ciferoj de la Brita Meteologia Oficejo indikas, ke la jaroj ekde 2000 estis meznombre 0,18 °C (0,32 ℉) pli varmaj ol la 1990-aj jaroj. Ekde la 1970-aj jaroj ĉiu jardeko vidas pliigon de proksimume la sama skalo. La unua jardeko de 21-a jarcento estas "nedisputeble" la plej varma ekde kalkuloj komenciĝis, deklaris en decembro 2009 la Brita Meteologia Oficejo kaj la Monda Organizaĵo pri Meteologio (mallonge: MOM). 2009 estis verŝajne la kvina plej varma en 160-jara observado. MOM sciigis, ke tutmondaj temperaturoj estas 0,44 °C (0,79 ℉) super la longatempa ordinara temperaturo. "Ni vidis superajn mezumajn temperaturojn en pluraj kontinentoj, kaj nur en Nordameriko regis kondiĉoj kun plu malvarmaj temperaturoj ol mezume," diris la Ĝenerala Sekretario de WMO Michel Jarraud. "Ni estas en varmiĝa tendenco - ni tute ne dubas pri tio."

Ĉe tio NASA sugestas, ke nova tutmonda temperaturrekordo estos "fiksita en la sekvontaj unu aŭ du jaroj", inkluzive de danke al influo de El Niño. Aliaj esploristoj, kvankam, kredas pli probable, ke temperaturoj restos stabilaj dum unu jardeko ĉar aliaj naturaj cikloj tenas la oceanan surfacon relative malvarmeta, rapida varmiĝo probable alvenos poste.[21]

Efikoj

Mediaj efikoj

La mediaj efikoj de la klimata ŝanĝo estas grandaj kaj longatingaj, damaĝante oceanojn, glacion kaj la veteron ĝenerale. Ŝanĝoj povas okazi laŭgrade aŭ rapide. La pruvaro por tiuj efikoj venas el studado de la klimata ŝanĝo en la pasinteco, el modelado, kaj el modernaj observoj.[22] Ekde la 1950-aj jaroj, sekego kaj varmondoj estis aperintaj samtempe kun pliiĝanta ofteco.[23] Ekstreme malsekaj aŭ sekaj eventoj ene de la periodo de la musono pliiĝis en Barato kaj en Orienta Azio.[24] La pluvindico kaj intenseco de uraganoj kaj tajfunoj plej verŝajne estas pliiĝanta,[25] kaj la geografia teritorio plej verŝajne estas etendiĝante al polusoj kiel konsekvenco de la klimata varmigo.[26] Ofteco de tropikaj ciklonoj ne pliiĝis kiel rezulto de la klimata ŝanĝo.[27]

Tutmonda marnivelo estas plialtiĝante kiel konsekvenco de la glacia fandiĝo, nome de la fandiĝo de la Gronlanda kaj de la Antarkta glacitavoloj, kaj de la termika etendo. Inter 1993 kaj 2020, la plialtiĝo pliiĝis laŭlonge de la tempo, averaĝe 3.3 ± 0.3 mm jare.[29] Laŭlonge de la 21a jarcento, la IPCC antaŭvidas, ke en supozebla okazo de tre altaj elsendoj la marnivelo povus plialtiĝi je 61–110 cm.[30] Pliiĝanta oceanvarmo estas malfortiĝanta kaj minacanta dispecigi la Antarktajn glaĉerpecojn, riskante grandan fandadon de la glacitavolo[31] kaj la eblon de 2-metra manivela plialtiĝo ĉirkaŭ 2100 se pluas altaj elsendoj.[32]

Klimata ŝanĝo kondukis al jardekoj de malpliiĝo kaj maldikiĝo de la Arkta glacitavolo.[33] Kvankam oni supozas, ke senglaciaj someroj estos raraj je 1.5 °C gradoj de varmiĝo, ili povus okazi unufoje ĉiun trian ĝis dekan jaron je varmiĝnivelo de 2 °C.[34] Pli altaj atmosferaj koncentriĝoj de CO2 kondukis al ŝanĝoj en la oceana kemikompono. Pliiĝo en la dissolvo de CO2 estas okazigante, ke oceanoj acidiĝas.[35] Krome, la oceanaj oksigen-niveloj estas malpliiĝantaj ĉar oksigeno estas malpli solvebla en pli varma akvo.[36] Tiel mortaj zonoj en la oceanoj, nome regionoj en kiuj estas malmulta oksigeno, estas etendiĝantaj.[37]

Riskopunktoj kaj longdaŭraj efikoj

Pli altaj gradoj de pliiĝo de tutmonda varmiĝo pliigas la riskon suferi riskopunktojn — sojloj trans kiuj precizaj efikoj ne plu estos eviteblaj eĉ se oni malaltigas la temperaturojn.[38][39] Ekzemplo estas la kolapso de la glacitavoloj de Okcidenta Antarkto kaj de Gronlando, kie temperatura plialtiĝo de 1.5 ĝis 2 °C povas fari, ke la glacitavoloj fandiĝu, kvankam la temposkalo de fandiĝo estas necerta kaj dependas de estonta plivarmiĝo.[40][41] Kelkaj grand-skalaj ŝanĝoj povas okazi subite en neatendite mallonga tempoperiodo, kiel malfunkciiĝo de kelkaj marfluoj kiel ĉe la Atlantika Turnofluo Sudena (AMOC).[42] Aliaj riskopunktoj povas esti ankaŭ nerenversebla damaĝo al ekosistemoj kiel ĉe la Amazona pluvarbaro kaj la koralrifoj.[43]

Inter long-daŭraj efikoj de la klimata ŝanĝo en oceanoj menciindas plue glacifando, oceanvarmiĝo, plialtigo de la marnivelo kaj la oceana acidiĝo.[44] Laŭ temposkalo de jarcentoj ĝis jarmiloj, la enormeco de la klimata ŝanĝo estas markita ĉefe de la antropogenaj elsendoj de CO2. Tio okazas pro la longa atmosfera vivodaŭro de la CO2.[45] La oceana enpreno de CO2 estas tiom malrapida ke la oceana acidiĝo pluos dum centoj ĝis miloj da jaroj.[46] Oni ĉirkaŭkalkulas, ke tiuj elsendoj estis plilongigintaj la nunan interglacian periodon ĉe almenaŭ 100 000 jaroj.[47] La plialtigo de la marnivelo pluos dum multaj jarcentoj, kaj oni ĉirkaŭkalkulis plialtiĝon de 2.3 m/ °C post 2000 jaroj.[48]

Naturo

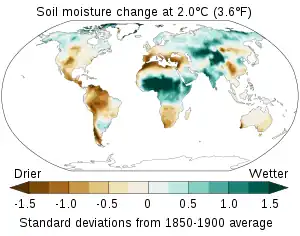

Lastatempa varmiĝo pelis multaj surterajn kaj nesalakvajn speciojn direkte al polusoj kaj al pli altaj altitudoj.[49] Pli altaj atmosferaj niveloj de CO2 kaj etendiĝintaj kreskosezono rezultis en tutmonda verdiĝo. Tamen, varmondoj kaj sekego estis malpliigintaj vla produktivecon de la ekosistemoj en kelkaj regionoj. La estonta ekvilibro de tiuj kontraŭaj efikoj ne estas klara.[50] La klimata ŝanĝo kontribuis al la ekspansio de pli sekaj klimataj zonoj, same kiel al la ekspansio de dezertoj en la subtropikoj.[51] La grando kaj rapido de la tutmonda varmiĝo estas faranta nedeziratajn subitajn ŝanĝojn en la ekosistemoj.[52] Ĝenerale, oni timas, ke la klimata ŝanĝo rezultos en la formorto de multaj specioj.[53]

La oceanoj varmiĝis pli malrapide ol la tero, sed plantoj kaj oceanaj animaloj estas migrantaj al la pli malvarmaj polusoj pli rapide ol la surteraj specioj.[54] Ĝuste same kiel surtere, varmondoj en la oceano okazas pli ofte pro la klimata ŝanĝo, damaĝante ampleksan gamon de organismoj kiel koraloj, algoj, kaj marbirdoj.[55] Oceana acidiĝo malhelpas la kalciiĝo de marorganismoj kiel mituloj, ciripedojs kaj koraloj por produkti ŝelojn kaj skeletojn; kaj varmondoj blankigis la koralrifojn.[56] Aperego de damaĝaj algoj helpita de la klimata ŝanĝo kaj de eŭtrofiĝo de pli malaltaj oksigenniveloj, damaĝas la manĝoretojn kaj okazigas grandan perdon de marvivantuloj.[57] La marbordaj ekosistemoj estas sub aparta danĝero. Preskaŭ la duono de la tutmondaj malsekejoj malaperis pro la klimata ŝanĝo kun aliaj efikoj de la homa agado.[58]

|

Homoj

La efikoj de la klimata ŝanĝo estas tuŝantaj homojn ie ajn en la momdo. La efikojn oni povas observi en ĉiuj kontinentoj kaj oceanaj regionoj,[65] kun malaltaj latitudoj, en kiuj malplej disvolviĝintaj areoj frontas la plej grandajn riskojn.[66] Kontinua varmiĝo eventuale okazigas "severajn, ĝeneralajn kaj nereverteblajn efikojn" por la personoj kaj por la ekosistemoj.[67] La riskoj estas malegale distribuataj, sed estas ĝenerale pli grandaj por la malriĉaj sociekonomiaj tavoloj kaj en disvolviĝantaj kaj en disvolvigitaj landoj.[68]

Manĝo kaj sano

La MOS klasigis la klimatan ŝanĝon kiel la plej granda minaco al la tutmonda sano en la 21-a jarcento.[69] Ekstrema vetero kondukas al mortoj kaj suferigoj,[70] kaj malsukcesoj de rikoltoj rezultas en malsufiĉa nutrado.[71] Variaj infektaj malsanoj estas pli facile transigeblaj en pli varma klimato, kiel la dengo kaj la malario.[72] Infanoj estas la plej vundeblaj pro malabundo de manĝaĵoj. Kaj infanoj kaj maljunuloj estas vundeblaj pro la ekstrema varmo.[73] La Monda Organizaĵo pri Sano (MOS) ĉirkaŭkalkulis, ke inter 2030 kaj 2050, la klimata ŝanĝo okazigos ĉirkaŭ 250 000 kromajn mortojn jare. Ili pritaksis mortojn pro ekspono al varmo ĉe plej aĝuloj, pliiĝoj en diareo, malario, dengo, en ĉemarbordaj inundoj, kaj pro malsufiĉa nutrado ĉe infanoj.[74] Oni ĉirkaŭkalkulis 500 000 kromajn mortojn de plenkreskuloj jare ĉirkaŭ 2050 pro la malpliiĝo de la manĝodisponeblo kaj de ĝia kvalito.[75] Ĉirkaŭ 2100, 50% ĝis 75% de la tutmonda populacio povus fronti klimatajn kondiĉojn kiuj estos viv-minacaj pro kombinitaj efikoj de ekstremaj varmo kaj humideco.[76]

La klimata ŝanĝo endanĝerigas la nutrosekurecon. Ĝi jam okazigis reduktadon en la tutmondaj rikoltoj de maizo, tritiko kaj sojo inter 1981 kaj 2010.[77] Estonta varmiĝo povus plue redukti la totalajn tutmondajn produktadojn de la ĉefaj manĝoproduktoj.[78] La agrikultura produktiveco probable estos negative tuŝita en landoj de malaltaj latitudoj, kvankam la efikoj en nordaj latitudoj povus esti ĉu pozitivaj ĉu negativaj.[79] Ĝis kromaj 183 milionoj da personoj tutmonde, precize ĉe tiuj de plej malaltaj enspezoj, estas je risko de malsatego kiel konsekvenco de tiuj efikoj.[80] La klimata ŝanĝo ankaŭ damaĝas la populaciojn de fiŝoj. Tutmonde, estos malpli da fiŝoj fiŝkapteblaj (fiŝkaptotaj).[81] Regionoj dependantaj de glaĉera akvo, regionoj kiuj estas jam sekaj, kaj malgrandaj kaj malaltaj insuloj havas pli altan riskon de akvomanko pro la klimata ŝanĝo.[82]

Rimedoj

Ekonomiaj perdoj pro la tutmonda varmiĝo povas esti severaj kaj estas eblo de katastrofaj konsekvencoj.[83] La klimata ŝanĝo plej verŝajne jam pliigis la tutmondan ekonomian malegalecon, kaj oni supozas, ke tiu tendenco kontinuos.[84] Oni supozas, ke plej el la severaj efikoj okazos en sub-Sahara Afriko, kie plej granda parto de lokanoj estas dependantaj el naturaj kaj agrikulturaj rimedoj,[85] kaj en Sudorienta Azio.[86] La Monda Banko ĉirkaŭkalkulas, ke la tutmonda varmiĝo povus meti ĉirkaŭ 120 milionojn da personoj en malriĉeco ĉirkaŭ 2030.[87]

Malegalecoj bazitaj sur la riĉeco kaj la socia statuso malboniĝis pro la tutmonda varmiĝo.[88] Ĉefaj malfacilaĵoj por mildigi, adaptiĝi kaj rekuperiĝi el frapoj de la klimata ŝanĝiĝoj estas suferataj de marĝenaj personoj kiuj havas malpli da kontrolo super rimedoj.[85][89] Indiĝenaj popoloj, kiuj eltenas sin pere de siaj teroj kaj ekosistemoj, frontos endanĝeriĝon el siaj bonfarto kaj vivostiloj pro la tutmonda varmiĝo.[90] Fakula esplorado konkludis, ke la rolo de la klimata ŝanĝo en la militoj estis malgrandaj kompare kun faktoroj kiel la soci-ekonomia malegaleco kaj la ŝtataj kapabloj.[91]

Malaltaj insuloj kaj marbordaj komunumoj estas minacataj de la plialtiĝo de la marnivelo, kii faras inundojn pli oftaj. Foje, la tero permanente perdiĝas al la maro.[92] Tio povus rezulti en la senŝtateco por popoloj el insulaj landoj, kiel Maldivoj and Tuvalo.[93] En kelkaj regionoj, la plialtiĝo de la temperaturo kaj de la humideco povus esti tro akra por ke homoj povu adaptiĝi al tio.[94] En la plej malbonaj de la antaŭsupozoj pri la tutmonda varmiĝo, modeloj supozas, ke preskaŭ unu triono de la homaro povus vivi en ekstreme varmaj kaj neloĝeblaj klimatoj, similaj al la klimato de Saharo.[95] Tiuj faktoroj povas rezulti en pro-media amasmigrado, kaj ene kaj inter landoj.[11] Oni timas, ke plej granda parto de la loĝantaroj estos translokigita pro l plialtiĝo de la marnivelo, la ekstrema vetero kaj konfliktoj pro pliiĝanta konkurenco por la naturaj rimedoj. La klimata ŝanĝo povus ankaŭ pliigi la vundebleco, knoduke al situacioj de "kaptitaj populacioj" kiuj ne kapablus translokiĝi pro manko de rimedoj, kio jam estas iel okazanta en la eksterleĝa migrado tra Mediteraneo en nehumanaj kondiĉoj, foje mortigaj.[96]

|

Indikoj

Neĝkovrilo de Kilimanĝaro

Laŭ konkludoj de la usona esploro publikigita la 2-an de novembro 2009 en la revuo "Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences" (esperante Diskutoj de la Nacia Scienca Akademio), la neĝoj ĉe la pinto de la monto degelas en 1912 ili estis 85 % pli granda ol en 2007, kaj inter 2000 kaj 2009 glacikovraĵo kuntiriĝis je 26 %. Aŭtoroj asertas, ke la neĝoj sur Kilimanĝaro povus malaperi entute post 20 jaroj. Laŭ ili ankaŭ maltrankviliga efiko estas la maldensiĝo de la glacikampoj sur la surfaco. La pintoj kaj de la norda kaj suda glacikampoj supre de Kilimanĝaro jam maldensiĝis je 1,9 metroj kaj 5,1 metroj respektive.

La pli malgranda Glaciejo Furtwangler, kiu estis degelanta kaj sekve plena de akvo en 2000 kiam ĝi estis borita, inter 2000 kaj 2009 maldensiĝis je 50 %. "Estonte, oni povas antaŭvidi, ke tiu glaciejo Furtwangler aperos unu jaron, kaj malaperos la sekvontan jaron", diris kunaŭtoro de la esploro Lonnie Thompson. La sciencistoj asertis, ke ili ne trovis pruvojn de daŭranta degelo aliloke en la eroj de la glacia kerno kiujn ili eltiris, kiuj datiĝas de 11 700 jaroj. Sekve la aktualaj klimataj kondiĉoj sur Kilimanĝaro estas unikaj dum la lastaj 11 jarmiloj.[102]

La glacikovraĵo de Gronlando

La raporto el 2007 de la Interregistara Spertularo pri klimata ŝanĝiĝo (angle IPCC) projektis altiĝon de marnivelo de inter 28 kaj 43 cm dum ĉi tiu jarcento. Sed ĝi agnoskis, ke ĉi tiu estas preskaŭ certe subtaksata cifero, ĉar kompreno de kiel glacio kondutas ne estis sufiĉe bona por fari fidindajn projekciojn.[103]

Analizo de satelitaj donitaĵoj, eldonitaj en septembro 2009, montris, ke el 111 rapide evoluantaj gronlandaj glaciejoj studitaj, 81 maldensiĝis dufoje pli rapide ol la malrapide movanta glacio apud ili. Ĉi tio indikas, ke la glaciejoj estas akcelantaj kaj ellasas pli da glacio en la ĉirkaŭantan maron.[103]

En novembro 2009 la revuo "Science" publikis esploron laŭ kiu la glacikovraĵo de Gronlando perdas sian amason pli rapide ol en antaŭaj jaroj, kio akcelas altiĝon de la marniveloj. Ĉiujare malaperas de 273 000 milionoj da tunoj da glacio. Por la periodo 2000-2008, degelo de gronlanda glacio altigis marnivelojn je mezume 0,46 mm ĉiun jaron. Ekde 2006 estas klara pliigo al 0,75 mm ĉiun jaron. "Sed ni havis tri tre varmajn somerojn, kaj tio estas akcelanta la degelon konsiderinde", diris la esploristo Michiel van den Broeke de la Universitato Utrecht (Nederlando). "Ĉu ĉi tio daŭros, mi ne povas diri, sed ni kompreneble atendas, ke la klimato fariĝos pli varma estonte." Entute, marniveloj estas altiĝantaj je proksimume 3 mm ĉiun jaron, ĉefe ĉar marakvo estas vastiĝanta samtempe kiam ĝi varmiĝas.

Degelo sur la glacia surfaco agas kiel "retro-mekanismo", Dro van den Broeke klarigis, ĉar la likva akvo sorbas pli kaj reflektas malpli de la envenanta sunradiado - kio rezultas je varmigo de la glacio. "Varmiĝo super Gronlando kaŭzis la pligravigon de degelo, kaj tio ankaŭ akcelas la retro-procezon," li diris. "Tre probable la oceanoj ankaŭ varmiĝis, kaj tio probable klarigas la akcelon de ellasejo de glaciejoj ĉar ili varmiĝis de malsupre."

La novaj esploroj montras, ke en Gronlando, proksimume duono de la perdo venas el pli rapida fluo al la oceanoj, kaj la alia duono venas el ŝanĝoj sur la glacikovraĵo mem, ĉefe surfaca degelo. Danke al la satelita misio Grace, uzita en ĉi tiu studo, estas konite, ke la plimulto de la amaso perdiĝas en la sudorienta, sudokcidenta kaj nordokcidenta partoj ĉe malaltaj altecoj kie la aero ĝenerale estas pli varma ol ĉe altaj altitudoj. Degelo de la tuta glacitavolo altigus marajn nivelojn tutmonde je proksimume 7 metroj.[103]

Konsekvencoj

Se la niveloj de oceanoj kaj maroj plialtiĝos pro tutmonda varmiĝo, tiam iuj insuloj kaj kontinentaj marbordoj subakviĝos, kaj sekve multaj homoj migros.

Pri la aktualaj marfluoj, de kiuj tre dependas multaj regionaj klimatoj, estas neniu certeco ke ili ne estas jam ekŝanĝiĝantaj kaj trajektorie kaj temperature. Tiaj ŝanĝoj povus kaŭzi estontece novajn klimatojn en kelkaj regionoj de la terglobo. La klimataj ŝanĝoj en tiuj regionoj kaŭzos perturbon en la ekologia sistemo, kaj al ĉiuj estaĵoj tie vivantaj.

En oktobro 2009 la brita ĉefministro Gordon Brown deklaris, ke Britio alfrontos "katastrofajn" inundojn, senpluvecon kaj varm-ondojn, se mondaj gvidantoj ne povas atingi interkonsenton pri klimata ŝanĝiĝo. Do, li diris al la Forumo de Gravaj Ekonomioj en Londono, kiu unuigas 17 el la mondaj plej grandaj produktantoj de forcejaj gasoj, ke "ne estas plano B". "La eksterordinara somera varmondo de 2003 en Eŭropo rezultis je super 35 000 ekstraj mortoj. Laŭ aktualaj tendencoj, tiela evento povus fariĝi tre rutina en Britio post nur kelkaj jardekoj. Kaj ene de la vivdaŭro de niaj infanoj kaj nepoj la varmegaj temperaturoj de 2003 povus fariĝi mezuma temperaturo vaste spertataj tra Eŭropo", diris Gordon Brown. Laŭ li, la kostoj de tiu estus pli granda ol la efikoj kaj de mondmilitoj kaj la Granda Depresio kombinitaj. La mondo alfrontus pli da konfliktoj estigitaj de vasta migrado pro klimatŝanĝiĝo kaj rezulte de tio en 2080 1,8 miliardo da homoj povus suferi pro manko de akvo.[104]

Neado

Kelkaj sektoroj ĉu de politikistoj ĉu de la industria etoso aktive propagandis kontraŭ la scienca evidento, ke ekzistas ĉu tutmonda varmiĝo ĉu almenaŭ klimata ŝanĝo. Tiuj politikaj sektoroj direktas sin al la dekstra flanko, dum la industridevena sektoro de neadistoj celas protekti sian interesojn super la ĝenerala bonfarto kaj rajto al akceptebla medio. Ankaŭ financistoj helpas tiun neadismon dupolusan (vidu ekzemple artikolon pri Familio Koch).

En Esperanto

- Amri Wandel, La klimatŝanĝa kulminkonferenco: ĉu la interkonsentoj sufiĉos por bremsi la varmiĝon?.[105]

Referencoj

- ↑ [Chapter 2: Observations: Atmosphere and Surface] Hartmann et al. 2013 http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/report/WG1AR5_Chapter02_FINAL.pdf FAQ 2.1, "Evidence for a warming world comes from multiple independent climate indicators, from high up in the atmosphere to the depths of the oceans. They include changes in surface, atmospheric and oceanic temperatures; glaciers; snow cover; sea ice; sea level and atmospheric water vapour. Scientists from all over the world have independently verified this evidence many times."

- ↑ Myth vs Facts..... EPA (US) (2013). Arkivita el la originalo je 2011-12-06. Alirita 2015-02-08.The U.S. Global Change Research Program, the National Academy of Sciences, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have each independently concluded that warming of the climate system in recent decades is 'unequivocal'. This conclusion is not drawn from any one source of data but is based on multiple lines of evidence, including three worldwide temperature datasets showing nearly identical warming trends as well as numerous other independent indicators of global warming (e.g., rising sea levels, shrinking Arctic sea ice).

- ↑ IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018, p. 54

- ↑ (19 October 2021) “Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature”, Environmental Research Letters 16 (11), p. 114005. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966.

- ↑ Our World in Data, 18 September 2020

- ↑ IPCC SRCCL 2019, p. 7; IPCC SRCCL 2019, p. 45

- ↑ IPCC SROCC 2019, p. 16

- ↑ IPCC AR6 WG1 Ch11 2021, p. 1517

- ↑ EPA (19 January 2017) Climate Impacts on Ecosystems. Arkivita el la originalo je 27a de Januaro 2018. Alirita 5a de Februaro 2019. “Mountain and arctic ecosystems and species are particularly sensitive to climate change... As ocean temperatures warm and the acidity of the ocean increases, bleaching and coral die-offs are likely to become more frequent.”.

- ↑ IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018, p. 64

- 1 2 Cattaneo et al. 2019; IPCC AR6 WG2 2022, paĝoj 15, 53

- ↑ IPCC AR5 SYR 2014, paĝoj 13–16; WHO, Nov 2015: "Climate change is the greatest threat to global health in the 21st century. Health professionals have a duty of care to current and future generations. You are on the front line in protecting people from climate impacts – from more heat-waves and other extreme weather events; from outbreaks of infectious diseases such as malaria, dengue and cholera; from the effects of malnutrition; as well as treating people who are affected by cancer, respiratory, cardiovascular and other non-communicable diseases caused by environmental pollution."

- ↑ IPCC AR6 WG2 2022, p. 19

- ↑ IPCC AR6 WG2 2022, paĝoj 21–26; 2504;IPCC AR6 SYR SPM 2023, paĝoj 8–9: "Effectiveness15 of adaptation in reducing climate risks16 is documented for specific contexts, sectors and regions (high confidence)...Soft limits to adaptation are currently being experienced by small-scale farmers and households along some low-lying coastal areas (medium confidence) resulting from financial, governance, institutional and policy constraints (high confidence). Some tropical, coastal, polar and mountain ecosystems have reached hard adaptation limits (high confidence). Adaptation does not prevent all losses and damages, even with effective adaptation and before reaching soft and hard limits (high confidence)."

- ↑ IPCC AR6 WG1 Technical Summary 2021, p. 71

- ↑ United Nations Environment Programme 2021, p. 36

- ↑ IPCC SR15 Ch2 2018, paĝoj 95–96; IPCC SR15 2018, SPM C.3; Rogelj et al. Riahi; Hilaire et al. 2019

- ↑ United Nations Environment Programme 2019, Table ES.3; Teske, ed. 2019, p. xxvii, Fig.5.

- ↑ United Nations Environment Programme 2019, Table ES.3 & p. 49; NREL 2017, paĝoj vi, 12

- ↑ IPCC SRCCL Summary for Policymakers 2019, p. 18

- ↑ Tiu ĉi jardeko estas rekorde varma Arkivigite je 2010-07-16 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine esperante

- ↑ Hansen et al. 2016; Smithsonian, 26 June 2016.

- ↑ USGCRP Chapter 15 2017, p. 415.

- ↑ Scientific American, 29 April 2014; Burke & Stott 2017.

- ↑ USGCRP Chapter 9 2017, p. 260.

- ↑ (29a de Decembro 2021) “Poleward expansion of tropical cyclone latitudes in warming climates”, Nature Geoscience 15, p. 14–28. doi:10.1038/s41561-021-00859-1.

- ↑ Hurricanes and Climate Change (10a de Julio 2020).

- ↑ NOAA 2017.

- ↑ WMO 2021, p. 12.

- ↑ IPCC SROCC Ch4 2019, p. 324: GMSL (global mean sea level, red) will rise between 0.43 m (0.29–0.59 m, likely range) (RCP2.6) and 0.84 m (0.61–1.10 m, likely range) (RCP8.5) by 2100 (medium confidence) relative to 1986–2005.

- ↑ DeConto & Pollard 2016.

- ↑ Bamber et al. 2019.

- ↑ Zhang et al. 2008

- ↑ IPCC SROCC Summary for Policymakers 2019, p. 18

- ↑ Doney et al. 2009.

- ↑ Deutsch et al. 2011

- ↑ IPCC SROCC Ch5 2019, p. 510; Climate Change and Harmful Algal Blooms. United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA]] (5a de Septembro 2013). Alirita 11a de Septembro 2020.

- ↑ IPCC SR15 Ch3 2018, p. 283.

- ↑ (9a de Septembro 2022) “Exceeding 1.5 °C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points”, Science (en) 377 (6611), p. eabn7950. doi:10.1126/science.abn7950.

- ↑ Tipping points in Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets (12a de Novembro 2018). Alirita 25a de Februaro 2019.

- ↑ IPCC SR15 Summary for Policymakers 2018, p. 7

- ↑ Clark et al. 2008

- ↑ Nine Tipping Points That Could Be Triggered by Climate Change. CarbonBrief (10a de Februaro 2020). Alirita 27a de Majo 2022.

- ↑ IPCC AR6 WG1 Summary for Policymakers 2021, p. 21

- ↑ IPCC AR5 WG1 Ch12 2013, FAQ 12.3

- ↑ IPCC AR5 WG1 Ch12 2013, p. 1112.

- ↑ Crucifix 2016

- ↑ Smith et al. 2009; Levermann et al. 2013

- ↑ IPCC SR15 Ch3 2018, p. 218.

- ↑ IPCC SRCCL Ch2 2019, p. 133.

- ↑ IPCC SRCCL Summary for Policymakers 2019, p. 7; Zeng & Yoon 2009.

- ↑ Turner et al. 2020, p. 1.

- ↑ Urban 2015.

- ↑ Poloczanska et al. 2013; Lenoir et al. 2020

- ↑ Smale et al. 2019

- ↑ IPCC SROCC Summary for Policymakers 2019, p. 13.

- ↑ IPCC SROCC Ch5 2019, p. 510

- ↑ IPCC SROCC Ch5 2019, p. 451.

- ↑ Coral Reef Risk Outlook. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2a de Januaro 2012). Alirita 4a de Aprilo 2020. “At present, local human activities, coupled with past thermal stress, threaten an estimated 75 percent of the world's reefs. By 2030, estimates predict more than 90% of the world's reefs will be threatened by local human activities, warming, and acidification, with nearly 60% facing high, very high, or critical threat levels.”.

- ↑ Carbon Brief, 7 January 2020.

- ↑ Turetsky et al. 2019

- ↑ IPCC AR5 WG2 Ch28 2014, p. 1596

- ↑ What a changing climate means for Rocky Mountain National Park. Nacia Parka Agentejo. Alirita 9a de Aprilo 2020.

- ↑ IPCC AR6 WG1 Summary for Policymakers 2021, Fig. SPM.6, page=SPM-23

- ↑ IPCC AR5 WG2 Ch18 2014, paĝoj 983, 1008

- ↑ IPCC AR5 WG2 Ch19 2014, p. 1077.

- ↑ IPCC AR5 SYR Summary for Policymakers 2014, SPM 2

- ↑ IPCC AR5 SYR Summary for Policymakers 2014, SPM 2.3

- ↑ WHO, Nov 2015

- ↑ IPCC AR5 WG2 Ch11 2014, paĝoj 720–723

- ↑ Costello et al. 2009; Watts et al. 2015; IPCC AR5 WG2 Ch11 2014, p. 713

- ↑ Watts et al. 2019, pp. 1836, 1848.

- ↑ Watts et al. 2019, pp. 1841, 1847.

- ↑ WHO 2014

- ↑ Springmann et al. 2016, p. 2; Haines & Ebi 2019

- ↑ IPCC AR6 WG2 2022, p. 988

- ↑ IPCC SRCCL Ch5 2019, p. 451.

- ↑ Zhao et al. 2017; IPCC SRCCL Ch5 2019, p. 439

- ↑ IPCC AR5 WG2 Ch7 2014, p. 488

- ↑ IPCC SRCCL Ch5 2019, p. 462

- ↑ IPCC SROCC Ch5 2019, p. 503.

- ↑ Holding et al. 2016; IPCC AR5 WG2 Ch3 2014, paĝoj 232–233.

- ↑ DeFries et al. 2019, p. 3; Krogstrup & Oman 2019, p. 10.

- ↑ Diffenbaugh & Burke 2019; The Guardian, 26 January 2015; Burke, Davis & Diffenbaugh 2018.

- 1 2 (2021) Women's leadership and gender equality in climate action and disaster risk reduction in Africa − A call for action. Accra: FAO & The African Risk Capacity (ARC) Group. doi:10.4060/cb7431en. ISBN 978-92-5-135234-2.

- ↑ IPCC AR5 WG2 Ch13 2014, paĝoj 796–797

- ↑ Hallegatte et al. 2016, p. 12.

- ↑ IPCC AR5 WG2 Ch13 2014, p. 796.

- ↑ Grabe, Grose kaj Dutt, 2014; FAO, 2011; FAO, 2021a; Fisher kaj Carr, 2015; IPCC, 2014; Resurrección et al., 2019; UNDRR, 2019; Yeboah et al., 2019.

- ↑ Climate Change | United Nations For Indigenous Peoples. Alirita 29a de Aprilo 2022.

- ↑ Mach et al. 2019.

- ↑ IPCC SROCC Ch4 2019, p. 328.

- ↑ UNHCR 2011, p. 3.

- ↑ Matthews 2018, p. 399.

- ↑ Balsari, Dresser & Leaning 2020

- ↑ Flavell 2014, p. 38; Kaczan & Orgill-Meyer 2020

- ↑ Serdeczny et al. 2016.

- ↑ IPCC SRCCL Ch5 2019, paĝoj 439, 464.

- ↑ Nacia Oceana kaj Atmosfera Administracio What is nuisance flooding?. Alirita 8a de Aprilo, 2020.

- ↑ Kabir et al. 2016.

- ↑ Van Oldenborgh et al. 2019.

- ↑ Neĝoj de Kilimanĝaro malaperos post 20 jaroj... Arkivigite je 2010-07-16 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine esperante

- 1 2 3 Gronlando degelas... Arkivigite je 2012-01-11 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine esperante

- ↑ Britio ĉe rando de natura katastrofo? esperante

- ↑ Amri Wandel, La klimatŝanĝa kulminkonferenco: ĉu la interkonsentoj sufiĉos por bremsi la varmiĝon?, En Esperanto, 1364(1) Januaro 2022, pp. 20-21.

Fontoj

Informoj IPCC

Fourth Assessment Report

- IPCC. (2007) Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88009-1.

- Le Treut, H.. (2007) “Chapter 1: Historical Overview of Climate Change Science”, IPCC AR4 WG1 2007, p. 93–127.

- Randall, D. A.. (2007) “Chapter 8: Climate Models and their Evaluation”, IPCC AR4 WG1 2007, p. 589–662.

- Hegerl, G. C.. (2007) “Chapter 9: Understanding and Attributing Climate Change”, IPCC AR4 WG1 2007, p. 663–745.

- IPCC. (2007) Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7.

Arkivigite je 2018-11-10 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine

- Rosenzweig, C.. (2007) “Chapter 1: Assessment of observed changes and responses in natural and managed systems”, IPCC AR4 WG2 2007, p. 79–131.

- Schneider, S. H.. (2007) “Chapter 19: Assessing key vulnerabilities and the risk from climate change”, IPCC AR4 WG2 2007, p. 779–810.

- IPCC. (2007) Climate Change 2007: Mitigation of Climate Change, Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88011-4.

Arkivigite je 2014-10-12 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine

- Rogner, H.-H.. (2007) “Chapter 1: Introduction”, IPCC AR4 WG3 2007, p. 95–116.

Fifth Assessment report

- IPCC. (2013) Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05799-9.

. AR5 Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis — IPCC

- IPCC. (2013) “Summary for Policymakers”, IPCC AR5 WG1 2013.

- Hartmann, D. L.. (2013) “Chapter 2: Observations: Atmosphere and Surface”, IPCC AR5 WG1 2013, p. 159–254.

- Rhein, M.. (2013) “Chapter 3: Observations: Ocean”, IPCC AR5 WG1 2013, p. 255–315.

- Masson-Delmotte, V.. (2013) “Chapter 5: Information from Paleoclimate Archives”, IPCC AR5 WG1 2013, p. 383–464.

- Bindoff, N. L.. (2013) “Chapter 10: Detection and Attribution of Climate Change: from Global to Regional”, IPCC AR5 WG1 2013, p. 867–952.

- Collins, M.. (2013) “Chapter 12: Long-term Climate Change: Projections, Commitments and Irreversibility”, IPCC AR5 WG1 2013, p. 1029–1136.

IPCC AR5 WG22014

- IPCC. (2014) Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects, Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05807-1.

. Chapters 1–20, SPM, and Technical Summary.

- Jiménez Cisneros, B. E.. (2014) “Chapter 3: Freshwater Resources”, IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014, p. 229–269.

- Porter, J. R.. (2014) “Chapter 7: Food Security and Food Production Systems”, IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014, p. 485–533.

- Smith, K. R.. (2014) “Chapter 11: Human Health: Impacts, Adaptation, and Co-Benefits”, In IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014, p. 709–754.

- Olsson, L.. (2014) “Chapter 13: Livelihoods and Poverty”, IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014, p. 793–832.

- Cramer, W.. (2014) “Chapter 18: Detection and Attribution of Observed Impacts”, IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014, p. 979–1037.

- Oppenheimer, M.. (2014) “Chapter 19: Emergent Risks and Key Vulnerabilities”, IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014, p. 1039–1099.

- IPCC. (2014) Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects, Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05816-3.

. Chapters 21–30, Annexes, and Index.

- Larsen, J. N.. (2014) “Chapter 28: Polar Regions”, IPCC AR5 WG2 B 2014, p. 1567–1612.

- IPCC. (2014) Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change, Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05821-7.

- Blanco, G.. (2014) “Chapter 5: Drivers, Trends and Mitigation”, IPCC AR5 WG3 2014, p. 351–411.

- Lucon, O.. (2014) “Chapter 9: Buildings”, IPCC AR5 WG3 2014.

- IPCC AR5 SYR. (2014) The Core Writing Team: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report, Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC.

- IPCC. (2014) “Summary for Policymakers”, IPCC AR5 SYR 2014.

- IPCC. (2014) “Annex II: Glossary”, IPCC AR5 SYR 2014.

Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 °C

- IPCC. (2018) Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- IPCC. (2018) “Summary for Policymakers”, IPCC SR15 2018, p. 3–24.

- Allen, M. R.. (2018) “Chapter 1: Framing and Context”, IPCC SR15 2018, p. 49–91.

- Rogelj, J.. (2018) “Chapter 2: Mitigation Pathways Compatible with 1.5 °C in the Context of Sustainable Development”, IPCC SR15 2018, p. 93–174.

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O.. (2018) “Chapter 3: Impacts of 1.5 °C Global Warming on Natural and Human Systems”, IPCC SR15 2018, p. 175–311.

- de Coninck, H.. (2018) “Chapter 4: Strengthening and Implementing the Global Response”, IPCC SR15 2018, p. 313–443.

- Roy, J.. (2018) “Chapter 5: Sustainable Development, Poverty Eradication and Reducing Inequalities”, IPCC SR15 2018, p. 445–538.

Special Report: Climate change and Land

- IPCC. (2019) IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse gas fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems. In press.

- IPCC. (2019) “Summary for Policymakers”, IPCC SRCCL 2019, p. 3–34.

- Jia, G.. (2019) “Chapter 2: Land-Climate Interactions”, IPCC SRCCL 2019, p. 131–247.

- Mbow, C.. (2019) “Chapter 5: Food Security”, IPCC SRCCL 2019, p. 437–550.

Special Report: The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate

- IPCC. (2019) IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. In press.

- IPCC. (2019) “Summary for Policymakers”, IPCC SROCC 2019, p. 3–35.

- Meredith, M.. (2019) “Chapter 3: Polar Regions”, IPCC SROCC 2019, p. 203–320.

- Oppenheimer, M.. (2019) “Chapter 4: Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities”, IPCC SROCC 2019, p. 321–445.

- Bindoff, N. L.. (2019) “Chapter 5: Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities”, IPCC SROCC 2019, p. 447–587.

Sixth Assessment Report

- IPCC. (2021) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press (In Press).

- IPCC. (2021) “Summary for Policymakers”, IPCC AR6 WG1 2021.

- Arias, Paola A.. (2021) “Technical Summary”, IPCC AR6 WG1 2021.

- Seneviratne, Sonia I.. (2021) “Chapter 11: Weather and climate extreme events in a changing climate”, IPCC AR6 WG1 2021.

- IPCC. (2022) Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC. (2022) Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC. (2022) “Summary for Policymakers”, IPCC AR6 WG3 2022.

- IPCC. (2023) “Summary for Policymakers”, IPCC AR6 SYR 2023.

Aliaj reviziitaj fontoj

- (1989) “Aerosols, Cloud Microphysics, and Fractional Cloudiness”, Science 245 (4923), p. 1227–1239. doi:10.1126/science.245.4923.1227.

- (2020) “Climate Change, Migration, and Civil Strife.”, Curr Environ Health Rep 7 (4), p. 404–414. doi:10.1007/s40572-020-00291-4.

- (2019) “Ice sheet contributions to future sea-level rise from structured expert judgment”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116 (23), p. 11195–11200. doi:10.1073/pnas.1817205116.

- (2019) “On the financial viability of negative emissions”, Nature Communications 10 (1), p. 1783. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09782-x.

- (2016) “Environmental impacts of high penetration renewable energy scenarios for Europe”, Environmental Research Letters 11 (1), p. 014012. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/11/1/014012.

- (2017) “Climate and environmental science denial: A review of the scientific literature published in 1990–2015”, Journal of Cleaner Production 167, p. 229–241. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.066.

- (2020) “"School Strike 4 Climate": Social Media and the International Youth Protest on Climate Change”, Media and Communication 8 (2), p. 208–218. doi:10.17645/mac.v8i2.2768.

- (2018) “Carbon capture and storage (CCS): the way forward”, Energy & Environmental Science 11 (5), p. 1062–1176. doi:10.1039/c7ee02342a.

- (2017) “Impact of Anthropogenic Climate Change on the East Asian Summer Monsoon”, Journal of Climate 30 (14), p. 5205–5220. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0892.1.

- (2018) “Large potential reduction in economic damages under UN mitigation targets”, Nature 557 (7706), p. 549–553. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0071-9.

- (1938) “The artificial production of carbon dioxide and its influence on temperature”, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 64 (275), p. 223–240. doi:10.1002/qj.49706427503.

- (2019) “Human Migration in the Era of Climate Change”, Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 13 (2), p. 189–206. doi:10.1093/reep/rez008.

- (2014) “Recent Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather”, Nature Geoscience 7 (9), p. 627–637. doi:10.1038/ngeo2234.

- (2009) “Managing the health effects of climate change”, The Lancet 373 (9676), p. 1693–1733. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60935-1.

- (2018) “Classifying drivers of global forest loss”, Science 361 (6407), p. 1108–1111. doi:10.1126/science.aau3445.

- (2009) “The contribution of manure and fertilizer nitrogen to atmospheric nitrous oxide since 1860”, Nature Geoscience 2, p. 659–662. doi:10.1016/j.chemer.2016.04.002.

- (2016) “Contribution of Antarctica to past and future sea-level rise”, Nature 531 (7596), p. 591–597. doi:10.1038/nature17145.

- (2018) “Methane Feedbacks to the Global Climate System in a Warmer World”, Reviews of Geophysics 56 (1), p. 207–250. doi:10.1002/2017RG000559.

- (2012) “Multicentennial variability of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation and its climatic influence in a 4000 year simulation of the GFDL CM2.1 climate model”, Geophysical Research Letters 39 (13), p. n/a. doi:10.1029/2012GL052107.

- (2011) “Climate-Forced Variability of Ocean Hypoxia”, Science 333 (6040), p. 336–339. doi:10.1126/science.1202422.

Arkivigite je 2016-05-09 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine

- (2019) “Global warming has increased global economic inequality”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116 (20), p. 9808–9813. doi:10.1073/pnas.1816020116.

- (2009) “Ocean Acidification: The Other CO2 Problem”, Annual Review of Marine Science 1 (1), p. 169–192. doi:10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163834.

- Fahey, D. W.. (2017) “Chapter 2: Physical Drivers of Climate Change”, In USGCRP2017.

- (2020) “AGU Centennial Grand Challenge: Volcanoes and Deep Carbon Global CO2 Emissions From Subaerial Volcanism. Recent Progress and Future Challenges”, Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 21 (3), p. e08690. doi:10.1029/2019GC008690.

- (2020) “The Structure of Climate Variability Across Scales”, Reviews of Geophysics 58 (2), p. e2019RG000657. doi:10.1029/2019RG000657.

- (2019) “Global Carbon Budget 2019”, Earth System Science Data 11 (4), p. 1783–1838. doi:10.5194/essd-11-1783-2019.

- (2016) “Making sense of the early-2000s warming slowdown”, Nature Climate Change 6 (3), p. 224–228. doi:10.1038/nclimate2938.

- (2019) “Reduction in surface climate change achieved by the 1987 Montreal Protocol”, Environmental Research Letters 14 (12), p. 124041. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab4874.

- (2003) “The Economics of the Kyoto Protocol”, World Economics 4 (3), p. 144–145.

- (2018) “Mobilising civil society: can the climate movement achieve transformational social change?”, Interface: A Journal for and About Social Movements 10. Alirita 12 April 2019..

- (2019) “Nudging out support for a carbon tax”, Nature Climate Change 9 (6), p. 484–489. doi:10.1038/s41558-019-0474-0.

- (2019) “The Imperative for Climate Action to Protect Health”, New England Journal of Medicine 380 (3), p. 263–273. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1807873.

- (2016) “Ice melt, sea level rise and superstorms: evidence from paleoclimate data, climate modeling, and modern observations that 2 °C global warming could be dangerous”, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 16 (6), p. 3761–3812. doi:10.5194/acp-16-3761-2016.

- (2018) “Internet Blogs, Polar Bears, and Climate-Change Denial by Proxy”, BioScience 68 (4), p. 281–287. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix133.

- (2017) “Estimating Changes in Global Temperature since the Preindustrial Period”, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 98 (9), p. 1841–1856. doi:10.1175/bams-d-16-0007.1.

- (2018) “A Revisit of Global Dimming and Brightening Based on the Sunshine Duration”, Geophysical Research Letters 45 (9), p. 4281–4289. doi:10.1029/2018GL077424.

- (17 October 2019) “Negative emissions and international climate goals—learning from and about mitigation scenarios”, Climatic Change 157 (2), p. 189–219. doi:10.1007/s10584-019-02516-4.

- (2009) “Climate Crisis? The Politics of Emergency Framing”, Economic and Political Weekly 44 (36), p. 53–60.

- (2016) “Groundwater vulnerability on small islands”, Nature Climate Change 6 (12), p. 1100–1103. doi:10.1038/nclimate3128.

- (2015) “Talking about Climate Change and Global Warming”, PLOS ONE 10 (9), p. e0138996. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138996.

- (2016) “Climate Change Impact: The Experience of the Coastal Areas of Bangladesh Affected by Cyclones Sidr and Aila”, Journal of Environmental and Public Health 2016, p. 9654753. doi:10.1155/2016/9654753.

- (2020) “The impact of climate change on migration: a synthesis of recent empirical insights”, Climatic Change 158 (3), p. 281–300. doi:10.1007/s10584-019-02560-0. Alirita 9 February 2021..

- (2010) “How do we know the world has warmed?”, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 91 (7). doi:10.1175/BAMS-91-7-StateoftheClimate.

- Kopp, R. E.. (2017) “Chapter 15: Potential Surprises: Compound Extremes and Tipping Elements”, In USGCRP 2017, p. 1–470.

- Kossin, J. P.. (2017) “Chapter 9: Extreme Storms”, In USGCRP2017, p. 1–470.

- Knutson, T.. (2017) “Appendix C: Detection and attribution methodologies overview.”, In USGCRP2017, p. 1–470.

- (July 2016) “Afforestation to mitigate climate change: impacts on food prices under consideration of albedo effects”, Environmental Research Letters 11 (8), p. 085001. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/11/8/085001.

- (2014) “The Aluminum Smelting Process”, Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 56 (5 Suppl), p. S2–S4. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000000154.

- (1998) “Arrhenius and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change”, Eos 79 (23), p. 271. doi:10.1029/98EO00206.

- (2013) “The multimillennial sea-level commitment of global warming”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (34), p. 13745–13750. doi:10.1073/pnas.1219414110.

- (2020) “Species better track climate warming in the oceans than on land”, Nature Ecology & Evolution 4 (8), p. 1044–1059. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-1198-2.

- (2009) “Do Models and Observations Disagree on the Rainfall Response to Global Warming?”, Journal of Climate 22 (11), p. 3156–3166. doi:10.1175/2008JCLI2472.1.

- (2009) “Conventions of climate change: constructions of danger and the dispossession of the atmosphere”, Journal of Historical Geography 35 (2), p. 279–296. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2008.08.008.

- (2021) “Satellite and Ocean Data Reveal Marked Increase in Earth's Heating Rate”, Geophysical Research Letters 48 (13). doi:10.1029/2021gl093047.

- (2019) “Climate as a risk factor for armed conflict”, Nature 571 (7764), p. 193–197. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1300-6.

- (2009) “The proportionality of global warming to cumulative carbon emissions”, Nature 459 (7248), p. 829–832. doi:10.1038/nature08047.

- (2018) “Humid heat and climate change”, Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 42 (3), p. 391–405. doi:10.1177/0309133318776490.

- (2017) “Atmospheric Aerosols: Clouds, Chemistry, and Climate”, Annual Review of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering 8 (1), p. 427–444. doi:10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-060816-101538.

- (2017) “Long-term pattern and magnitude of soil carbon feedback to the climate system in a warming world”, Science 358 (6359), p. 101–105. doi:10.1126/science.aan2874.

- (2018) “Macroeconomic impact of stranded fossil fuel assets”, Nature Climate Change 8 (7), p. 588–593. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0182-1.

- (2018) “Climate-change–driven accelerated sea-level rise detected in the altimeter era”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (9), p. 2022–2025. doi:10.1073/pnas.1717312115.

- ((National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine)) (2019). “Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda”. doi:10.17226/25259.

- National Research Council. (2011) “Causes and Consequences of Climate Change”, America's Climate Choices. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/12781. ISBN 978-0-309-14585-5.

- (2019a) “No evidence for globally coherent warm and cold periods over the preindustrial Common Era”, Nature 571 (7766), p. 550–554. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1401-2.

- (2019b) “Consistent multidecadal variability in global temperature reconstructions and simulations over the Common Era”, Nature Geoscience 12 (8), p. 643–649. doi:10.1038/s41561-019-0400-0.

- (2010) “Climate denier, skeptic, or contrarian?”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 (39), p. E151. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010507107.

- (2013) “Global imprint of climate change on marine life”, Nature Climate Change 3 (10), p. 919–925. doi:10.1038/nclimate1958.

- (2007) “Recent Climate Observations Compared to Projections”, Science 316 (5825), p. 709. doi:10.1126/science.1136843.

- (2008) “Global and Regional Climate Changes due to Black Carbon”, Nature Geoscience 1 (4), p. 221–227. doi:10.1038/ngeo156.

- (2009) “An update of observed stratospheric temperature trends”, Journal of Geophysical Research 114 (D2), p. D02107. doi:10.1029/2008JD010421. HAL 00355600.

- (2020) “Coal-exit health and environmental damage reductions outweigh economic impacts”, Nature Climate Change 10 (4), p. 308–312. doi:10.1038/s41558-020-0728-x.

- (2019) “Estimating and tracking the remaining carbon budget for stringent climate targets”, Nature 571 (7765), p. 335–342. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1368-z.

- (2015) “Impact of short-lived non-CO2 mitigation on carbon budgets for stabilizing global warming”, Environmental Research Letters 10 (7), p. 1–10. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/10/7/075001.

- (2020) “Rethinking standards of permanence for terrestrial and coastal carbon: implications for governance and sustainability”, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 45, p. 69–77. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2020.09.009.

- (2018) “Climate Impacts From a Removal of Anthropogenic Aerosol Emissions”, Geophysical Research Letters 45 (2), p. 1020–1029. doi:10.1002/2017GL076079.

- (2015) “Response of Arctic temperature to changes in emissions of short-lived climate forcers”, Nature 6 (3), p. 286–289. doi:10.1038/nclimate2880.

- (2010) “Attribution of the present-day total greenhouse effect”, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 115 (D20), p. D20106. doi:10.1029/2010JD014287.

- (2014) “Reconciling warming trends”, Nature Geoscience 7 (3), p. 158–160. doi:10.1038/ngeo2105.

- (2016) “Climate change impacts in Sub-Saharan Africa: from physical changes to their social repercussions”, Regional Environmental Change 17 (6), p. 1585–1600. doi:10.1007/s10113-015-0910-2.

- (2007) “Land/sea warming ratio in response to climate change: IPCC AR4 model results and comparison with observations”, Geophysical Research Letters 34 (2), p. L02701. doi:10.1029/2006GL028164.

- (2019) “Marine heatwaves threaten global biodiversity and the provision of ecosystem services”, Nature Climate Change 9 (4), p. 306–312. doi:10.1038/s41558-019-0412-1.

- (2009) “Assessing dangerous climate change through an update of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 'reasons for concern'”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (11), p. 4133–4137. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812355106.

- (2013) “The role of emotion in global warming policy support and opposition.”, Risk Analysis 34 (5), p. 937–948. doi:10.1111/risa.12140.

- (2016) “Global and regional health effects of future food production under climate change: a modelling study”, Lancet 387 (10031), p. 1937–1946. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01156-3.

- (2007) “Arctic sea ice decline: Faster than forecast”, Geophysical Research Letters 34 (9), p. L09501. doi:10.1029/2007GL029703.

- (2016) “Disentangling greenhouse warming and aerosol cooling to reveal Earth's climate sensitivity”, Nature Geoscience 9 (4), p. 286–289. doi:10.1038/ngeo2670.

- (2019) “Permafrost collapse is accelerating carbon release”, Nature 569 (7754), p. 32–34. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-01313-4.

- (2020) “Climate change, ecosystems and abrupt change: science priorities”, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 375 (1794). doi:10.1098/rstb.2019.0105.

- (1977) “The Influence of Pollution on the Shortwave Albedo of Clouds”, J. Atmos. Sci. 34 (7), p. 1149–1152. doi:[[doi:10.1175%2F1520-0469%281977%29034%3C1149%3ATIOPOT%3E2.0.CO%3B2|10.1175/1520-0469(1977)034<1149:TIOPOT>2.0.CO;2]].

- (1861) “On the Absorption and Radiation of Heat by Gases and Vapours, and on the Physical Connection of Radiation, Absorption, and Conduction”, Philosophical Magazine 22, p. 169–194, 273–285.

- (2015) “Accelerating extinction risk from climate change”, Science 348 (6234), p. 571–573. doi:10.1126/science.aaa4984.

- USGCRP. (2009) Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-14407-0.

Arkivigite je 2010-04-06 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine

- USGCRP. (2017) Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume I. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Global Change Research Program. doi:10.7930/J0J964J6.

- (2018) “Air quality co-benefits for human health and agriculture counterbalance costs to meet Paris Agreement pledges”, Nature Communications 9 (4939), p. 4939. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06885-9.

- Wuebbles, D. J.. (2017) “Chapter 1: Our Globally Changing Climate”, In USGCRP2017.

- Walsh, John. (2014) “Appendix 3: Climate Science Supplement”, Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment.

- (2017) “Sensitivity of global greenhouse gas budgets to tropospheric ozone pollution mediated by the biosphere”, Environmental Research Letters 12 (8), p. 084001. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aa7885.

- (2015) “Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health”, The Lancet 386 (10006), p. 1861–1914. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60854-6.

- (2019) “The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate”, The Lancet 394 (10211), p. 1836–1878. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32596-6.

- (2013) “Rise of interdisciplinary research on climate”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, p. 3657–3664. doi:10.1073/pnas.1107482109.

- (2005) “From Dimming to Brightening: Decadal Changes in Solar Radiation at Earth's Surface”, Science 308 (5723), p. 847–850. doi:10.1126/science.1103215.

- (2020) “Controls of the transient climate response to emissions by physical feedbacks, heat uptake and carbon cycling”, Environmental Research Letters 15 (9), p. 0940c1. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab97c9.

- (2015) “Feedbacks on climate in the Earth system: introduction”, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 373 (2054), p. 20140428. doi:10.1098/rsta.2014.0428.

- (2009) “Expansion of the world's deserts due to vegetation-albedo feedback under global warming”, Geophysical Research Letters 36 (17), p. L17401. doi:10.1029/2009GL039699.

- (2008) “What drove the dramatic arctic sea ice retreat during summer 2007?”, Geophysical Research Letters 35 (11), p. 1–5. doi:10.1029/2008gl034005.

- (2017) “Temperature increase reduces global yields of major crops in four independent estimates”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (35), p. 9326–9331. doi:10.1073/pnas.1701762114.

Libroj, informoj kaj juraj dokumentoj

- G8+5 Academies' joint statement: Climate change and the transformation of energy technologies for a low carbon future. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (Majo 2009). Arkivita el la originalo je 15a de Februaro 2010. Alirita 5a de Majo 2010.

- Archer, David. (2013) The Warming Papers: The Scientific Foundation for the Climate Change Forecast. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-68733-8.

- (Junio 2019) “Fossil Fuel to Clean Energy Subsidy Swaps”.

- Climate Focus (December 2015) The Paris Agreement: Summary. Climate Focus Client Brief on the Paris Agreement III. Arkivita el la originalo je 5 October 2018. Alirita 12a de Aprilo 2019.

Arkivigite je 2018-10-05 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine

- Clark, P. U.. (December 2008) “Executive Summary”, In: Abrupt Climate Change. A Report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey.

- Conceição (2020). “Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene”. Alirita 9a de Januaro 2021..

- (September 2019) “The missing economic risks in assessments of climate change impacts”.

- Dessler, Andrew E. kaj Edward A. Parson, eld. The science and politics of global climate change: A guide to the debate (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

- . The climate regime from The Hague to Marrakech: Saving or sinking the Kyoto Protocol?. Tyndall Centre Working Paper 12. Tyndall Centre (2001). Arkivita el la originalo je 10 June 2012. Alirita 5a de Majo 2010.

Arkivigite je 2012-06-10 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine

- Dunlap, Riley E.. (2011) “Chapter 10: Organized climate change denial”, The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society. Oxford University Press, p. 144–160. ISBN 978-0-19-956660-0.

- Dunlap, Riley E.. (2015) “Chapter 10: Challenging Climate Change: The Denial Countermovement”, Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives. Oxford University Press, p. 300–332. ISBN 978-0199356119.

- European Commission (28a de Novembro 2018). “In-depth analysis accompanying the Commission Communication COM(2018) 773: A Clean Planet for all – A European strategic long-term vision for a prosperous, modern, competitive and climate neutral economy”, p. 188.

- Fleming, James Rodger. (2007) The Callendar Effect: the life and work of Guy Stewart Callendar (1898–1964). Boston: American Meteorological Society. ISBN 978-1-878220-76-9.

- (Januaro 2021) “Peoples' Climate Vote”. Alirita 5a de Aŭgusto 2021..

- Global Methane Initiative (2020). “Global Methane Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities”.

- Hallegatte, Stephane. (2016) Shock Waves : Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty. Climate Change and Development. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-0673-5. ISBN 978-1-4648-0674-2.

- Haywood, Jim. (2016) “Chapter 27 – Atmospheric Aerosols and Their Role in Climate Change”, Climate Change: Observed Impacts on Planet Earth. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-63524-2.

- IEA (December 2020). “Energy Efficiency 2020”. Alirita 6a de Aprilo 2021..

- IEA (Oktobro 2021). “Net Zero By 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector”. Alirita 4a de Aprilo 2022..

- Krogstrup, Signe. (4 September 2019) Macroeconomic and Financial Policies for Climate Change Mitigation: A Review of the Literature, IMF working papers. doi:10.5089/9781513511955.001. ISBN 978-1-5135-1195-5.

- (2021) “International Public Opinion on Climate Change”. Alirita 5a de Aŭgusto 2021..

- (2020) Future Energy: Improved, Sustainable and Clean Options for our Planet. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-102886-5.

- Meinshausen, Malte. (2019) “Implications of the Developed Scenarios for Climate Change”, Achieving the Paris Climate Agreement Goals: Global and Regional 100% Renewable Energy Scenarios with Non-energy GHG Pathways for +1.5 °C and +2 °C. Springer International Publishing, p. 459–469. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-05843-2_12. ISBN 978-3-030-05843-2.

- (2017) “Impacts of World-Class Vehicle Efficiency and Emissions Regulations in Select G20 Countries”.

- Müller, Benito. (February 2010) Copenhagen 2009: Failure or final wake-up call for our leaders? EV 49. Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. ISBN 978-1-907555-04-6.

- National Academies (2008). “Understanding and responding to climate change: Highlights of National Academies Reports, 2008 edition”. Alirita 9 November 2010..

Arkivigite je 2017-10-11 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine

- National Research Council (2012). “Climate Change: Evidence, Impacts, and Choices”. Alirita 9 September 2017..

Arkivigite je 2013-02-20 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine

- Newell, Peter. (14 December 2006) Climate for Change: Non-State Actors and the Global Politics of the Greenhouse. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02123-4.

- NOAA January 2017 analysis from NOAA: Global and Regional Sea Level Rise Scenarios for the United States. Arkivita el la originalo je 18 December 2017. Alirita 7 February 2019.

- Olivier, J. G. J.. (2019) Trends in global CO2 and total greenhouse gas emissions. PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency.

- Oreskes, Naomi. (2007) “The scientific consensus on climate change: How do we know we're not wrong?”, Climate Change: What It Means for Us, Our Children, and Our Grandchildren. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-54193-0.

- Oreskes, Naomi. (2010) Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming. Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-59691-610-4.

- Pew Research Center (November 2015). “Global Concern about Climate Change, Broad Support for Limiting Emissions”. Alirita 5a de Aŭgusto 2021..

- REN21. (2020) Renewables 2020 Global Status Report. Paris: REN21 Secretariat. ISBN 978-3-948393-00-7.

- Royal Society. (13a de Aprilo 2005) Economic Affairs – Written Evidence, The Economics of Climate Change, the Second Report of the 2005–2006 session, produced by the UK Parliament House of Lords Economics Affairs Select Committee. UK Parliament.

- Setzer, Joana. (July 2019) Global trends in climate change litigation: 2019 snapshot. London: the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and the Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy.

- (2019) “Executive Summary”, Achieving the Paris Climate Agreement Goals: Global and Regional 100% Renewable Energy Scenarios with Non-energy GHG Pathways for +1.5 °C and +2 °C. Springer International Publishing, p. xiii–xxxv. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-05843-2. ISBN 978-3-030-05843-2.

- Teske, Sven. (2019) “Energy Scenario Results”, Achieving the Paris Climate Agreement Goals: Global and Regional 100% Renewable Energy Scenarios with Non-energy GHG Pathways for +1.5 °C and +2 °C. Springer International Publishing, p. 175–402. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-05843-2_8. ISBN 978-3-030-05843-2.

- Teske, Sven. (2019) “Trajectories for a Just Transition of the Fossil Fuel Industry”, Achieving the Paris Climate Agreement Goals: Global and Regional 100% Renewable Energy Scenarios with Non-energy GHG Pathways for +1.5 °C and +2 °C. Springer International Publishing, p. 403–411. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-05843-2_9. ISBN 978-3-030-05843-2.

- UN FAO (2016). “Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. How are the world's forests changing?”. Alirita 1 December 2019..

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2019) Emissions Gap Report 2019. ISBN 978-92-807-3766-0.

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2021) Emissions Gap Report 2021. ISBN 978-92-807-3890-2.

- UNEP. (2018) The Adaptation Gap Report 2018. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). ISBN 978-92-807-3728-8.

- UNFCCC (1997) Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. United Nations.

- UNFCCC (30a de Marto 2010). “Report of the Conference of the Parties on its fifteenth session, held in Copenhagen from 7 to 19 December 2009”. FCCC/CP/2009/11/Add.1. Alirita 17 May 2010..

- UNFCCC (2015) Paris Agreement. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

- UNFCCC (26a de Februaro 2021). “Nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement Synthesis report by the secretariat”.

- . Climate Change and the Risk of Statelessness: The Situation of Low-lying Island States. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (Majo 2011). Arkivita el la originalo je 2 May 2013. Alirita 13a de Aprilo 2012.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (2016). “Methane and Black Carbon Impacts on the Arctic: Communicating the Science”. Alirita 27 February 2019..

- (2019) “Human contribution to the record-breaking June 2019 heat wave in France”.

- Weart, Spencer. (Oktobro 2008) The Discovery of Global Warming, 2‑a eldono, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03189-0.

- Weart, Spencer. (Februaro 2019) The Discovery of Global Warming.

- Weart, Spencer (Januaro 2020), "The Carbon Dioxide Greenhouse Effect", The Discovery of Global Warming, American Institute of Physics, http://history.aip.org/climate/co2.htm, retrieved 19a de Junio 2020

- Weart, Spencer (Januaro 2020), "The Public and Climate Change", The Discovery of Global Warming, American Institute of Physics, http://history.aip.org/climate/public.htm, retrieved 19a de Junio 2020

- Weart, Spencer (Januaro 2020), "The Public and Climate Change: Suspicions of a Human-Caused Greenhouse (1956–1969)", The Discovery of Global Warming, American Institute of Physics, http://history.aip.org/climate/public.htm#S2, retrieved 19a de Junio 2020

- Weart, Spencer (Januaro 2020), "The Public and Climate Change (cont. – since 1980)", The Discovery of Global warming, American Institute of Physics, https://history.aip.org/climate/public2.htm, retrieved 19a de Junio 2020

- Weart, Spencer (Januaro 2020), "The Public and Climate Change: The Summer of 1988", The Discovery of Global Warming, American Institute of Physics, http://history.aip.org/climate/public2.htm#S1988, retrieved 19a de Junio 2020

- (June 2019) “State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2019”. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1435-8.

- World Health Organization (2014). “Quantitative risk assessment of the effects of climate change on selected causes of death, 2030s and 2050s”.

- World Health Organization (2016). “Ambient air pollution: a global assessment of exposure and burden of disease”.

- World Health Organization. (2018) COP24 Special Report Health and Climate Change. ISBN 978-92-4-151497-2.

- Monda Organizaĵo pri Meteologio. (2021) WMO Statement on the State of the Global Climate in 2020, WMO-No. 1264. ISBN 978-92-63-11264-4.

- World Resources Institute. (December 2019) Creating a Sustainable Food Future: A Menu of Solutions to Feed Nearly 10 Billion People by 2050. ISBN 978-1-56973-953-2.

Neteknikaj fontoj

- Associated Press

- . An addition to AP Stylebook entry on global warming (22a de Septembro 2015). Alirita 6a de Novembro 2019.

- BBC

- "UK Parliament declares climate change emergency", BBC, 1 May 2019.

- . Climate change: should we change the terminology? (3a de Februaro 2020). Alirita 24a de Marto 2020.

- Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

- "The global warming 'hiatus'", Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 23a de Septembro 2014.

- Carbon Brief

- . Clean energy: The challenge of achieving a 'just transition' for workers (4a de Januaro 2017). Alirita 18a de Majo 2020.

- Q&A: How do climate models work? (15a de Januaro 2018). Arkivita el la originalo je 5a de Marto 2019. Alirita 2a de Marto 2019.

- Explainer: How 'Shared Socioeconomic Pathways' explore future climate change (19a de Aprilo 2018). Alirita 20a de Julio 2019.

- Analysis: Why the IPCC 1.5C report expanded the carbon budget (8a de Oktobro 2018). Alirita 28a de Julio 2020.

- Media reaction: Australia's bushfires and climate change (7a de Januaro 2020). Alirita 11a de Januaro 2020.

- Climate.gov

- . Climate Change: Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide (23a de Junio 2022). Alirita 7a de Majo 2023.

- Deutsche Welle

- "Climate Action: Can We Change the Climate From the Grassroots Up?", Ecowatch, 22a de Junio 2019.

- EPA

- Myths vs. Facts: Denial of Petitions for Reconsideration of the Endangerment and Cause or Contribute Findings for Greenhouse Gases under Section 202(a) of the Clean Air Act. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (25a de Aŭgusto 2016). Alirita 7a de Aŭgusto 2017.

- US EPA (13a de Septembro 2019) Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data. Arkivita el la originalo je 18a de Februaro 2020. Alirita 8a de Aŭgusto 2020.

- US EPA (15a de Septembro 2020) Overview of Greenhouse Gases. Alirita 15a de Septembro 2020.

- EUobserver

- Copenhagen failure 'disappointing', 'shameful' (20a de Decembro 2009). Arkivita el la originalo je 12a de Aprilo 2019. Alirita 12a de Aprilo 2019.

- Eŭropa Parlamento

- . Renewable Energy (Februaro 2020). Alirita 3a de Junio 2020.

- The Guardian

- "Climate change could impact the poor much more than previously thought", 26a de Januaro 2015.

- Carrington, Damian, "School climate strikes: 1.4 million people took part, say campaigners", 19a de Marto 2019.

- Rankin, Jennifer, "'Our house is on fire': EU parliament declares climate emergency", The Guardian, 28a de Novembro 2019.

- Watts, Jonathan, "Oil and gas firms 'have had far worse climate impact than thought'", 19a de Februaro 2020.

- . New renewable energy capacity hit record levels in 2019. The Guardian (6a de Aprilo 2020). Alirita 25a de Majo 2020.

- . South Korea vows to go carbon neutral by 2050 to fight climate emergency. The Guardian (28a de Oktobro 2020). Alirita 6a de Decembro 2020.

- Internacia Energia Agentejo

- Projected Costs of Generating Electricity 2020. Alirita 4a de Aprilo 2022.

- NASA

- "Arctic amplification", NASA.

- Carlowicz, Michael, "Watery heatwave cooks the Gulf of Maine", NASA's Earth Observatory, 12a de Septembro 2018.

- . What's in a Name? Global Warming vs. Climate Change. NASA (5a de Decembro 2008). Arkivita el la originalo je 9a de Aŭgusto 2010.

- The Carbon Cycle: Feature Articles: Effects of Changing the Carbon Cycle. Earth Observatory, part of the EOS Project Science Office located at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (16a de Junio 2011). Arkivita el la originalo je 6a de Februaro 2013. Alirita 4a de Februaro 2013.

- What's in a name? Weather, global warming and climate change (Januaro 2016). Arkivita el la originalo je 28a de Septembro 2018. Alirita 12a de Oktobro 2018.

- Overview: Weather, Global Warming and Climate Change (7 July 2020). Alirita 14 July 2020.

- National Conference of State Legislators

- State Renewable Portfolio Standards and Goals (17a de Aprilo 2020). Alirita 3a de Junio 2020.

- National Geographic

- . Arctic permafrost is thawing fast. That affects us all. (13a de Aŭgusto 2019). Alirita 25a de Aŭgusto 2019.

- National Science Digital Library

- . Climate Change and Anthropogenic Greenhouse Warming: A Selection of Key Articles, 1824–1995, with Interpretive Essays (17a de Marto 2008). Alirita 7a de Oktobro 2019.

- Natural Resources Defense Council

- What Is the Clean Power Plan? (29a de Septembro 2017). Alirita 3a de Aŭgusto 2020.

- Nature

- (2016) “Earth's narrow escape from a big freeze”, Nature 529 (7585), p. 162–163. doi:10.1038/529162a.

- The New York Times

- Rudd, Kevin, "Paris Can't Be Another Copenhagen", The New York Times, 25a de Majo 2015.

- NOAA

- NOAA (10a de Julio 2011) Polar Opposites: the Arctic and Antarctic. Arkivita el la originalo je 22a de Februaro 2019. Alirita 20a de Februaro 2019.

- . Happy 200th birthday to Eunice Foote, hidden climate science pioneer (17a de Julio 2019). Alirita 8a de Oktobro 2019.

- Our World in Data

- (15a de Januaro 2018) “Land Use”, Our World in Data. Alirita 1a de Decembro 2019..

- Sector by sector: where do global greenhouse gas emissions come from? (18a de Septembro 2020). Alirita 28a de Oktobro 2020.

- Why did renewables become so cheap so fast? (2022). Alirita 4a de Aprilo 2022.

- Pew Research Center

- Pew Research Center (16a de Oktobro 2020) Many globally are as concerned about climate change as about the spread of infectious diseases. Alirita 19a de Aŭgusto 2021.

- Politico

- Europe's Green Deal plan unveiled (11a de Decembro 2019). Alirita 29a de Decembro 2019.

- Salon,com

- Leopold, Evelyn, "How leaders planned to avert climate catastrophe at the UN (while Trump hung out in the basement)", 25a de Septembro 2019.

- ScienceBlogs

- "Statements on Climate Change from Major Scientific Academies, Societies, and Associations (January 2017 update)", ScienceBlogs, 7a de Januaro 2017.

- Scientific American

- Ogburn, Stephanie Paige (29a de Aprilo 2014). "Indian Monsoons Are Becoming More Extreme". Scientific American. Arkivita el la originalo la 22an de Junio 2018.

- gazeto Smithsonian

- . Studying the Climate of the Past Is Essential for Preparing for Today's Rapidly Changing Climate (29a de Junio 2016). Alirita 8a de Novembro 2019.

- The Sustainability Consortium

- One-Fourth of Global Forest Loss Permanent: Deforestation Is Not Slowing Down (13a de Septembro 2018). Alirita 1a de Decembro 2019.

- UN Environment

- Curbing environmentally unsafe, irregular and disorderly migration (25a de Oktobro 2018). Arkivita el la originalo je 18a de Aprilo 2019. Alirita 18a de Aprilo 2019.

- UNFCCC

- What are United Nations Climate Change Conferences?. Arkivita el la originalo je 12a de Majo 2019. Alirita 12a de Majo 2019.

- Unio de Koncernitaj Sciencistoj

- Carbon Pricing 101 (8a de Januaro 2017). Alirita 15a de Majo 2020.

- gazeto Vice

- "The UK Has Declared a Climate Emergency: What Now?", 2a de Majo 2019.

- The Verge

- . 2019 was the year of 'climate emergency' declarations (27a de Decembro 2019). Alirita 28a de Marto 2020.

- Vox

- Getting to 100% renewables requires cheap energy storage. But how cheap? (20a de Septembro 2019). Alirita 28a de Mayjo 2020.

- Monda Organizaĵo pri Sano

- WHO calls for urgent action to protect health from climate change – Sign the call (Novembro 2015). Arkivita el la originalo je 3a de Januaro 2021. Alirita 2a de Septembro 2020.

- Instituto pri Mondaj Rimedoj

- "Global forest loss increases in 2020", Mongabay, 31a de Marto 2021.

- Mongabay graphing WRI data from Forest Loss / How much tree cover is lost globally each year?. World Resources Institute — Global Forest Review (Januaro 2021). Arkivita el la originalo je 10a de Marto 2021.

- (8a de Aŭgusto 2019) “How Effective Is Land At Removing Carbon Pollution? The IPCC Weighs In”. Alirita 15a de Majo 2020..

- (8a de Decembro 2019) “Forests in the IPCC Special Report on Land Use: 7 Things to Know”.

- Yale Climate Connections

- . Yale Researcher Anthony Leiserowitz on Studying, Communicating with American Public. Yale Climate Connections (2a de Novembro 2010). Arkivita el la originalo je 7a de Februaro 2019. Alirita 30a de Julio 2018.

Literaturo

- Terri Adams–Fuller, "Dangerous Discomfort: Extreme heat kills more people in the U.S. than hurricanes, flash floods and tornadoes combined. But people don't tend to believe it puts them at risk", Scientific American, vol. 329, no. 1 (Julio/Aŭgusto 2023), pp. 64–69.

- Parshley, Lois, "When Disaster Strikes, Is Climate Change to Blame?", Scientific American, vol. 328, no. 6 (Junio 2023), pp. 44–51.

Vidu ankaŭ

- Greta Thunberg

- Al Gore

- Vendredojn por la estonteco

- Extinction Rebellion

- Alternatiba, vilaĝo de alternativoj

- Biciklo

- Holarkta ekozono

- Interregistara Spertularo pri Klimata Ŝanĝiĝo

- "La tago post morgaŭ" ("The Day After Tomorrow"), filmo

- Senarbarigo

- Marnivela leviĝo

- Renoviĝanta energio

- Klimata ŝanĝiĝo

- Klimata justeco

- Naturmediaj efikoj de viandoproduktado

Eksteraj ligiloj

- NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies – Global change research

- NOAA State of the Climate Report – U.S. and global monthly state of the climate reports

- Climate Change at the National Academies Arkivigite je 2015-05-02 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine – repository for reports

- Nature Reports Climate Change – libera aliro

- Met Office: Climate change Arkivigite je 2010-11-27 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine ;– UK National Weather Service

- Educational Global Climate Modelling Arkivigite je 2015-03-23 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine (EdGCM) – research-quality climate change simulator

- Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison Arkivigite je 2017-01-24 per la retarkivo Wayback Machine Develops and releases standardized models such as CMIP3 (AR4) and CMIP5 (AR5)

- En tiu ĉi artikolo estas uzita traduko de teksto el la artikolo Climate change en la angla Vikipedio.

.jpg.webp)