Essigsäurepropylester

Essigsäurepropylester (nach IUPAC-Nomenklatur Propylethanoat, auch Essigsäure-n-propylester oder Propylacetat) ist ein Carbonsäureester, der sich aus Essigsäure und 1-Propanol zusammensetzt. Zusammen mit der isomeren Verbindung Essigsäureisopropylester bildet er die Gruppe der Propylacetate.

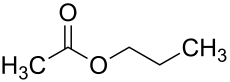

| Strukturformel | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allgemeines | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Name | Essigsäurepropylester | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Andere Namen | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summenformel | C5H10O2 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Kurzbeschreibung |

flüchtige, farblose Flüssigkeit mit fruchtigem Geruch[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Externe Identifikatoren/Datenbanken | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eigenschaften | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molare Masse | 102,13 g·mol−1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Aggregatzustand |

flüssig[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dichte |

0,89 g·cm−3 (20 °C)[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Schmelzpunkt | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Siedepunkt |

102 °C[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dampfdruck | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Löslichkeit | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brechungsindex |

1,3844[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sicherheitshinweise | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| MAK | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Toxikologische Daten | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Soweit möglich und gebräuchlich, werden SI-Einheiten verwendet. Wenn nicht anders vermerkt, gelten die angegebenen Daten bei Standardbedingungen. Brechungsindex: Na-D-Linie, 20 °C | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Vorkommen

Essigsäurepropylester kommt im Aroma vieler Früchte vor. Ein wichtiger Bestandteil ist es im Apfelaroma[7][8], wo es bis zu 10 % der flüchtigen Verbindungen ausmacht.[9] Beispielsweise wurde es in den Sorten Golden Delicious und Granny Smith nachgewiesen.[10][11] Es ist ebenso ein wichtiger Bestandteil im Aroma von Hancornia speciosa (bis zu 11 %)[12] und von Pflaumen.[13] Es kommt außerdem vor in Zuckermelonen[14][15][16], Nektarinen[17][18], Passionsfrucht[19], Papaya,[20] Erdbeeren,[21] Feigen,[22] Pfirsich[23], Guaven[24] und Wein[25][26][27], sowie in Saft von Himbeeren, Brombeeren und Pfirsich.[28][29] In kleinen Mengen wurde es in Ananas[30][31], Bananen[32] und Jackfrucht[33] nachgewiesen. Außerdem ist es mitverantwortlich für den Geruch von Grassilage.[34]

Apfel

Apfel Hancornia speciosa

Hancornia speciosa Pflaumen

Pflaumen Zuckermelone

Zuckermelone Nektarinen

Nektarinen

Gewinnung und Darstellung

Die technische Herstellung von Essigsäurepropylester erfolgt weitestgehend durch direkte Veresterung von Essigsäure mit 1-Propanol bei Temperaturen von 90–120 °C an stark sauren Kationenaustauschern als Katalysator.[35]

Die Umsetzung wird in einem rohrförmigen Festbettreaktor durchgeführt und das entstehende Wasser kontinuierlich aus dem Reaktionsgemisch entfernt (Verschiebung des Gleichgewichts auf die Produktseite).[35]

Im Labor- bzw. kleinerem Maßstab verwendet man gelegentlich auch starke Mineralsäuren wie Schwefel- oder Salzsäure, sowie oft auch p-Toluolsulfonsäure als Katalysator.[36] Essigsäurepropylester kann auch enzymatisch hergestellt werden, durch Umesterung von Vinylacetat mit 1-Propanol.[37]

Eigenschaften

Physikalische Eigenschaften

Essigsäurepropylester ist eine farblose Flüssigkeit, die bei Normaldruck bei 101,5 °C siedet.[38] Die molare Verdampfungsenthalpie beträgt am Siedepunkt 33,92 kJ·mol−1.[39] Die Dampfdruckfunktion ergibt sich nach Antoine entsprechend log10(P) = A−(B/(T+C)) (P in bar, T in K) mit A = 4,14386, B = 1283,861 und C = −64,378 im Temperaturbereich von 312,22 bis 374,03 K.[40] Es besitzt eine spezifische Wärmekapazität bei 25 °C von 196,07 J·K−1·mol−1 bzw. 1,92 J·K−1·g−1[41], eine Oberflächenspannung von 24,28 mN/m, eine Standardverdampfungsenthalpie von 39,77 kJ/mol[39], eine Dielektrizitätszahl von 6,002 und eine Viskosität von 0,58 mPa·s (jeweils bei 20 °C).

Sicherheitstechnische Kenngrößen

Essigsäurepropylester bildet leicht entzündliche Dampf-Luft-Gemische. Die Verbindung hat einen Flammpunkt bei 10 °C.[2][42] Der Explosionsbereich liegt zwischen 1,7 Vol.‑% (70 g/m3) als untere Explosionsgrenze (UEG) und 8,0 Vol.‑% (340 g/m3) als obere Explosionsgrenze (OEG).)[2] Der maximale Explosionsdruck beträgt 8,6 bar.[2] Die Grenzspaltweite wurde mit 1,04 mm bestimmt.[2][42] Es resultiert damit eine Zuordnung in die Explosionsgruppe IIA.[2] Die Zündtemperatur beträgt 455 °C.[2][42] Der Stoff fällt somit in die Temperaturklasse T1.

Verwendung

Essigsäurepropylester ist eines der wichtigsten Lösungsmittel in der Druckindustrie.[43][44] Auch in der Kosmetikindustrie wird es als Lösungsmittel verwendet, dort überwiegend in Nagellack-Produkten.[45][46][47] Beim Voluntary Cosmetic Registration Program der FDA im Jahr 2010 wurden beispielsweise insgesamt 46 Produkte registriert, die die Verbindung enthalten, darunter auch 26 von 333 Nagellack-Produkten.[48]

Daneben wird es in Kosmetika auch als Duftstoff verwendet.[49][47] Seine Geruchsschwelle beträgt 2000 μL/m3.[50] Es ist zum Beispiel eine wichtige Geruchskomponente in Duftkerzen mit Apfelaroma.[51] In Lebensmitteln wird es als Aroma eingesetzt, bei der FDA ist es GRAS (generally recognized as safe)[48], in der EU ist es unter der FL-Nummer 09.002 für Lebensmittel allgemein zugelassen.[52]

Als Elektrolyt in Lithium-Ionen-Batterien wird vor allem Ethylencarbonat eingesetzt, eine Verwendung von Essigsäurepropylester, insbesondere zum Einsatz bei tiefen Temperaturen, wird jedoch erforscht.[53]

Toxikologie / Risikobewertung

Die Verbindung wird im menschlichen Körper zu Essigsäure und 1-Propanol metabolisiert. Die akute Toxizität von Essigsäurepropylester ist sehr gering.[48] In verschiedenen Studien wurde der LD50-Wert bestimmt, zu 9,37 g/kg Körpergewicht (Ratte, oral)[54], 8,3 g/kg (Maus oral)[54], sowie größer 5 g/kg (Kaninchen, dermal).[48] In geringen und mäßigen Mengen verursachte die Verbindung keine Hautreizungen in Versuchen an Tieren und Menschen, in sehr hohen Mengen (10 mL/kg an Meerschweinchen) verursachte es deutliche, vorübergehende Reizungen oder (20 mL/kg an Kaninchen) zum Teil sogar Nekrosen.[48] In Versuchen an Kaninchen verursachte es leichte Augenreizungen. In zwei Studien konnte keine Genotoxizität festgestellt werden.[48] Die Dämpfe von Essigsäurepropylester wirken auf Menschen narkotisierend.

Essigsäurepropylester wurde 2015 von der EU gemäß der Verordnung (EG) Nr. 1907/2006 (REACH) im Rahmen der Stoffbewertung in den fortlaufenden Aktionsplan der Gemeinschaft (CoRAP) aufgenommen. Hierbei werden die Auswirkungen des Stoffs auf die menschliche Gesundheit bzw. die Umwelt neu bewertet und ggf. Folgemaßnahmen eingeleitet. Ursächlich für die Aufnahme von Essigsäurepropylester waren die Besorgnisse bezüglich Verbraucherverwendung, Exposition von Arbeitnehmern, hoher (aggregierter) Tonnage, anderer gefahrenbezogener Bedenken und weit verbreiteter Verwendung sowie der möglichen Gefahr durch reproduktionstoxische Eigenschaften. Die Neubewertung wurde zurückgezogen.[55]

Weblinks

- Eintrag zu Propyl acetate in der Spectral Database for Organic Compounds (SDBS) des National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST)

Einzelnachweise

- Eintrag zu PROPYL ACETATE in der CosIng-Datenbank der EU-Kommission, abgerufen am 29. Juni 2020.

- Eintrag zu Propylacetat in der GESTIS-Stoffdatenbank des IFA, abgerufen am 8. Januar 2020. (JavaScript erforderlich)

- BASF: n-Propyl Acetate, abgerufen am 2. Februar 2020.

- Wilhelm Riemenschneider, Hermann M. Bolt: Esters, Organic. In: Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA., 30. April 2005, S. 247, doi:10.1002/14356007.a09_565.pub2.

- Eintrag zu Propyl acetate im Classification and Labelling Inventory der Europäischen Chemikalienagentur (ECHA), abgerufen am 1. Februar 2016. Hersteller bzw. Inverkehrbringer können die harmonisierte Einstufung und Kennzeichnung erweitern.

- Schweizerische Unfallversicherungsanstalt (Suva): Grenzwerte – Aktuelle MAK- und BAT-Werte (Suche nach 109-60-4 bzw. Essigsäure-n-propylester), abgerufen am 2. November 2015.

- Kiichi Nishimura, Yoshio Hirose: The Aroma Constituents of “KOGYOKU” Apple. In: Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. Band 28, Nr. 1, Januar 1964, S. 1–4, doi:10.1080/00021369.1964.10858201.

- M.L. LóPez, M.T. Lavilla, M. Riba, M. Vendrell: COMPARISON OF VOLATILE COMPOUNDS IN TWO SEASONS IN APPLES: GOLDEN DELICIOUS AND GRANNY SMITH. In: Journal of Food Quality. Band 21, Nr. 2, April 1998, S. 155–166, doi:10.1111/j.1745-4557.1998.tb00512.x.

- S. Kondo, S. Setha, D.R. Rudell, D.A. Buchanan, J.P. Mattheis: Aroma volatile biosynthesis in apples affected by 1-MCP and methyl jasmonate. In: Postharvest Biology and Technology. Band 36, Nr. 1, April 2005, S. 61–68, doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2004.11.005.

- M.L. LóPez, M.T. Lavilla, M. Riba, M. Vendrell: COMPARISON OF VOLATILE COMPOUNDS IN TWO SEASONS IN APPLES: GOLDEN DELICIOUS AND GRANNY SMITH. In: Journal of Food Quality. Band 21, Nr. 2, April 1998, S. 155–166, doi:10.1111/j.1745-4557.1998.tb00512.x.

- M?L Lopez, M?T Lavilla, I Recasens, J Graell, M Vendrell: Changes in aroma quality of ?Golden Delicious? apples after storage at different oxygen and carbon dioxide concentrations. In: Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. Band 80, Nr. 3, Februar 2000, S. 311–324, doi:10.1002/1097-0010(200002)80:3<311::AID-JSFA519>3.0.CO;2-F.

- Taís Santos Sampaio, Paulo Cesar L. Nogueira: Volatile components of mangaba fruit (Hancornia speciosa Gomes) at three stages of maturity. In: Food Chemistry. Band 95, Nr. 4, April 2006, S. 606–610, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.01.038.

- Jorge Antonio Pino, Clara Elizabeth Quijano: Study of the volatile compounds from plum (Prunus domestica L. cv. Horvin) and estimation of their contribution to the fruit aroma. In: Food Science and Technology. Band 32, Nr. 1, 31. Januar 2012, S. 76–83, doi:10.1590/S0101-20612012005000006.

- Javier M. Obando-Ulloa, Bart Nicolai, Jeroen Lammertyn, María C. Bueso, Antonio J. Monforte, J. Pablo Fernández-Trujillo: Aroma volatiles associated with the senescence of climacteric or non-climacteric melon fruit. In: Postharvest Biology and Technology. Band 52, Nr. 2, Mai 2009, S. 146–155, doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2008.11.007.

- Ana L Amaro, Joana F Fundo, Ana Oliveira, John C Beaulieu, Juan Pablo Fernández-Trujillo, Domingos PF Almeida: 1-Methylcyclopropene effects on temporal changes of aroma volatiles and phytochemicals of fresh-cut cantaloupe: 1-Methylcyclopropene effects on aroma volatiles and phytochemicals of cantaloupe. In: Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. Band 93, Nr. 4, 15. März 2013, S. 828–837, doi:10.1002/jsfa.5804.

- Javier M. Obando-Ulloa, Eduard Moreno, Jordi García-Mas, Bart Nicolai, Jeroen Lammertyn, Antonio J. Monforte, J. Pablo Fernández-Trujillo: Climacteric or non-climacteric behavior in melon fruit. In: Postharvest Biology and Technology. Band 49, Nr. 1, Juli 2008, S. 27–37, doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2007.11.004.

- T Lavilla, I Recasens, M?L Lopez, J Puy: Multivariate analysis of maturity stages, including quality and aroma, in ?Royal Glory? peaches and ?Big Top? nectarines. In: Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. Band 82, Nr. 15, Dezember 2002, S. 1842–1849, doi:10.1002/jsfa.1268.

- J. Cano-Salazar, M.L. López, C.H. Crisosto, G. Echeverría: Volatile compound emissions and sensory attributes of ‘Big Top’ nectarine and ‘Early Rich’ peach fruit in response to a pre-storage treatment before cold storage and subsequent shelf-life. In: Postharvest Biology and Technology. Band 76, Februar 2013, S. 152–162, doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2012.10.001.

- Natália S. Janzantti, Magali Monteiro: Changes in the aroma of organic passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims f. flavicarpa Deg.) during ripeness. In: LWT - Food Science and Technology. Band 59, Nr. 2, Dezember 2014, S. 612–620, doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2014.07.044.

- David B. Katague, Ernst R. Kirch: Chromatographic Analysis of the Volatile Components of Papaya Fruit. In: Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. Band 54, Nr. 6, Juni 1965, S. 891–894, doi:10.1002/jps.2600540616.

- Dangyang Ke, Lili Zhou, Adel A. Kader: Mode of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide Action on Strawberry Ester Biosynthesis. In: Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. Band 119, Nr. 5, September 1994, S. 971–975, doi:10.21273/JASHS.119.5.971.

- W Jennings: Volatile components of figs. In: Food Chemistry. Band 2, Nr. 3, Juli 1977, S. 185–191, doi:10.1016/0308-8146(77)90032-2.

- J. Cano-Salazar, M.L. López, C.H. Crisosto, G. Echeverría: Volatile compound emissions and sensory attributes of ‘Big Top’ nectarine and ‘Early Rich’ peach fruit in response to a pre-storage treatment before cold storage and subsequent shelf-life. In: Postharvest Biology and Technology. Band 76, Februar 2013, S. 152–162, doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2012.10.001.

- Charng Cherng. Chyau, Shu Yueh. Chen, Chung May. Wu: Differences of volatile and nonvolatile constituents between mature and ripe guava (Psidium guajava Linn.) fruits. In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. Band 40, Nr. 5, Mai 1992, S. 846–849, doi:10.1021/jf00017a028.

- Kemal Şen: The influence of different commercial yeasts on aroma compounds of rosé wine produced from cv. Öküzgözü grape. In: Journal of Food Processing and Preservation. Band 45, Nr. 7, Juli 2021, doi:10.1111/jfpp.15610.

- Juan J. Moreno, Carmen Millán, José M. Ortega, Manuel Medina: Analytical differentiation of wine fermentations using pure and mixed yeast cultures. In: Journal of Industrial Microbiology. Band 7, Nr. 3, April 1991, S. 181–189, doi:10.1007/BF01575881.

- C. E. Daudt, C. S. Ough: A Method for Quantitative Measurement of Volatile Acetate Esters from Wine. In: American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. Band 24, Nr. 3, 1973, S. 125–129, doi:10.5344/ajev.1973.24.3.125.

- Laura Vázquez-Araújo, Edgar Chambers IV, Koushik Adhikari, Ángel A. Carbonell-Barrachina: Sensory and Physicochemical Characterization of Juices Made with Pomegranate and Blueberries, Blackberries, or Raspberries. In: Journal of Food Science. Band 75, Nr. 7, September 2010, S. S398–S404, doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01779.x.

- Montserrat Riu-Aumatell, Elvira López-Tamames, Susana Buxaderas: Assessment of the Volatile Composition of Juices of Apricot, Peach, and Pear According to Two Pectolytic Treatments. In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. Band 53, Nr. 20, 1. Oktober 2005, S. 7837–7843, doi:10.1021/jf051397z.

- S. Elss, C. Preston, C. Hertzig, F. Heckel, E. Richling, P. Schreier: Aroma profiles of pineapple fruit (Ananas comosus [L.] Merr.) and pineapple products. In: LWT - Food Science and Technology. Band 38, Nr. 3, Mai 2005, S. 263–274, doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2004.07.014.

- Julio César Barros‐Castillo, Montserrat Calderón‐Santoyo, Luis Fernando Cuevas‐Glory, Carolina Calderón‐Chiu, Juan Arturo Ragazzo‐Sánchez: Contribution of glycosidically bound compounds to aroma potential of jackfruit ( Artocarpus heterophyllus lam). In: Flavour and Fragrance Journal. Band 38, Nr. 3, Mai 2023, S. 193–203, doi:10.1002/ffj.3730.

- María J. Jordán, Kawaljit Tandon, Philip E. Shaw, Kevin L. Goodner: Aromatic Profile of Aqueous Banana Essence and Banana Fruit by Gas Chromatography−Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) and Gas Chromatography−Olfactometry (GC-O). In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. Band 49, Nr. 10, 1. Oktober 2001, S. 4813–4817, doi:10.1021/jf010471k.

- Julio César Barros‐Castillo, Montserrat Calderón‐Santoyo, Luis Fernando Cuevas‐Glory, Carolina Calderón‐Chiu, Juan Arturo Ragazzo‐Sánchez: Contribution of glycosidically bound compounds to aroma potential of jackfruit ( Artocarpus heterophyllus lam). In: Flavour and Fragrance Journal. Band 38, Nr. 3, Mai 2023, S. 193–203, doi:10.1002/ffj.3730.

- M.E. Morgan, R.L. Pereira: Volatile Constituents of Grass and Corn Silage. II. Gas-entrained Aroma. In: Journal of Dairy Science. Band 45, Nr. 4, April 1962, S. 467–471, doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(62)89428-4.

- Patent EP0066059B1: Verfahren zur Veresterung von Essigsäure mit C2- bis C5-Alkoholen. Veröffentlicht am 28. November 1984, Anmelder: Chemische Werke Hüls AG, Erfinder: Helmut Alfs, Werner Böxkes, Erwin Vangermain.

- Eintrag zu Propylacetat. In: Römpp Online. Georg Thieme Verlag, abgerufen am 21. November 2018.

- Paramita Mahapatra, Annapurna Kumari, Vijay Kumar Garlapati, Rintu Banerjee, Ahindra Nag: Enzymatic synthesis of fruit flavor esters by immobilized lipase from Rhizopus oligosporus optimized with response surface methodology. In: Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic. Band 60, Nr. 1-2, September 2009, S. 57–63, doi:10.1016/j.molcatb.2009.03.010.

- V. Svoboda, F. Veselý, R. Holub, J. Pick: Heats of vaporization of alkyl acetates and propionates. In: Collection of Czechoslovak Chemical Communications. Band 42, Nr. 3, 1977, S. 943–951, doi:10.1135/cccc19770943.

- Majer, V.; Svoboda, V.: Enthalpies of Vaporization of Organic Compounds: A Critical Review and Data Compilation, Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, 1985, 300.

- Polák, J.; Mertl, I.: Saturated vapour pressure of methyl acetate, ethyl acetate, n-propyl acetate, methyl propionate, and ethyl propionate in Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 30 (1965) 3526–3528, doi:10.1135/cccc19653526.

- Jimenez, E.; Romani, L.; Paz Andrade, M.I.; Roux-Desgranges, G.; Grolier, J.-P.E.: Molar excess heat capacities and volumes for mixtures of alkanoates with cyclohexane at 25°C in J. Solution Chem. 15 (1986) 879–890, doi:10.1007/BF00646029.

- E. Brandes, W. Möller: Sicherheitstechnische Kenngrößen. Band 1: Brennbare Flüssigkeiten und Gase. Wirtschaftsverlag NW – Verlag für neue Wissenschaft, Bremerhaven 2003.

- Marmara University, School of Applied Science, Department of Printing Technologies, Istanbul, Turkey, Cem Aydemir, Samed Ayhan Özsoy, Istanbul University Cerrahpasa, Vocational School of Technical Sciences, Printing and Publication Technologies Program, Istanbul, Turkey: Environmental impact of printing inks and printing process. In: Journal of graphic engineering and design. Band 11, Nr. 2, Dezember 2020, S. 11–17, doi:10.24867/JGED-2020-2-011.

- Winchester, R. V. "Solvent exposure of workers during printing ink manufacture." The Annals of occupational hygiene 29.4 (1985): 517-519.

- Lexuan Zhong, Stuart Batterman, Chad W. Milando: VOC sources and exposures in nail salons: a pilot study in Michigan, USA. In: International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. Band 92, Nr. 1, Januar 2019, S. 141–153, doi:10.1007/s00420-018-1353-0, PMID 30276513, PMC 6325001 (freier Volltext).

- Tasha Heaton, Laura K. Hurst, Azita Amiri, Claudiu T. Lungu, Jonghwa Oh: Laboratory Estimation of Occupational Exposures to Volatile Organic Compounds During Nail Polish Application. In: Workplace Health & Safety. Band 67, Nr. 6, Juni 2019, S. 288–293, doi:10.1177/2165079918821701.

- Bart Heldreth, Wilma F. Bergfeld, Donald V. Belsito, Ronald A. Hill, Curtis D. Klaassen, Daniel Liebler, James G. Marks, Ronald C. Shank, Thomas J. Slaga, Paul W. Snyder, F. Alan Andersen: Final Report of the Cosmetic Ingredient Review Expert Panel on the Safety Assessment of Methyl Acetate. In: International Journal of Toxicology. Band 31, 4_suppl, August 2012, S. 112S–136S, doi:10.1177/1091581812444142.

- Bart Heldreth, Wilma F. Bergfeld, Donald V. Belsito, Ronald A. Hill, Curtis D. Klaassen, Daniel Liebler, James G. Marks, Ronald C. Shank, Thomas J. Slaga, Paul W. Snyder, F. Alan Andersen: Final Report of the Cosmetic Ingredient Review Expert Panel on the Safety Assessment of Methyl Acetate. In: International Journal of Toxicology. Band 31, 4_suppl, August 2012, S. 112S–136S, doi:10.1177/1091581812444142.

- David R Bickers, Peter Calow, Helmut A Greim, Jon M Hanifin, Adrianne E Rogers, Jean-Hilaire Saurat, I Glenn Sipes, Robert L Smith, Hachiro Tagami: The safety assessment of fragrance materials. In: Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. Band 37, Nr. 2, April 2003, S. 218–273, doi:10.1016/S0273-2300(03)00003-5.

- Gary Takeoka, Ron G. Buttery, Louisa Ling: Odour Thresholds of Various Branched and Straight Chain Acetates. In: LWT - Food Science and Technology. Band 29, Nr. 7, November 1996, S. 677–680, doi:10.1006/fstl.1996.0105.

- Gerhard Buchbauer, Leopold Jirovetz, Michael Wasicky, Alexej Nikiforov: Volatiles of cold and burning fragrance candles with lavender and apple aromas. In: Flavour and Fragrance Journal. Band 10, Nr. 4, Juli 1995, S. 233–237, doi:10.1002/ffj.2730100402.

- Food and Feed Information Portal Database | FIP. Abgerufen am 30. August 2023.

- Hiroki Nagano, Hackho Kim, Suguru Ikeda, Seiji Miyoshi, Motonori Watanabe, Tatsumi Ishihara: Ethylene Carbonate (EC)-Propyl Acetate (PA) Based Electrolyte for Low Temperature Performance of Li-Ion Rechargeable Batteries. In: Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. Band 94, Nr. 9, 15. September 2021, S. 2202–2209, doi:10.1246/bcsj.20210185.

- P.M. Jenner, E.C. Hagan, Jean M. Taylor, E.L. Cook, O.G. Fitzhugh: Food flavourings and compounds of related structure I. Acute oral toxicity. In: Food and Cosmetics Toxicology. Band 2, Januar 1964, S. 327–343, doi:10.1016/S0015-6264(64)80192-9.

- Community rolling action plan (CoRAP) der Europäischen Chemikalienagentur (ECHA): propyl acetate, abgerufen am 28. November 2023.